The Representation of African American Women in Silent Film

by Barbara Tepa Lupack

In the new genre of “race movies” created in the 1910s and 1920s, early independent race filmmakers attempted to counter the negative imagery with more realistic depictions of Black Americans and to establish new character types and situations. Seen by Black audiences, largely unseen by whites, race movies featured Black actresses and actors and incorporated timely and often controversial themes. And they depicted a virtually all-Black world, one with which Black moviegoers, particularly the growing number of Black female attendees, could identify. While race films did not, by any means, shatter the racial clichés or halt the offensive imagery that dominated American film, they offered a clear alternative to those troubling depictions and challenged other movie producers to strive for more balanced racial and ethnic portrayals in their pictures.

Race films countered the degrading imagery of early cinema’s “reel” Blacks with honest depictions of “real” Blacks.

About the Presenter

-

Barbara Tepa Lupack

Barbara Tepa Lupack, former professor of English and academic dean at SUNY, was Fulbright Professor of American Literature both in Poland and in France. From 2015-2018, she served as New York State Public Scholar. She was also the Helm Fellow at Indiana University (2013), the Lehman Fellow at the Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies (2014), and the Senior Fellow at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, MA (2017-2018). She is author or editor of more than twenty-five books, including Literary Adaptations in Black American Cinema: From Micheaux to Morrison (University of Rochester Press, 2002; expanded ed., 2010), Richard E. Norman and Race Filmmaking (Indiana University Press, 2013), Early Race Filmmaking in America (Routledge, 2016), Silent Serial Sensations: The Wharton Brothers and The Magic of Early Filmmaking (Cornell University Press, 2020), and a forthcoming study of the representation of women in silent film.

-

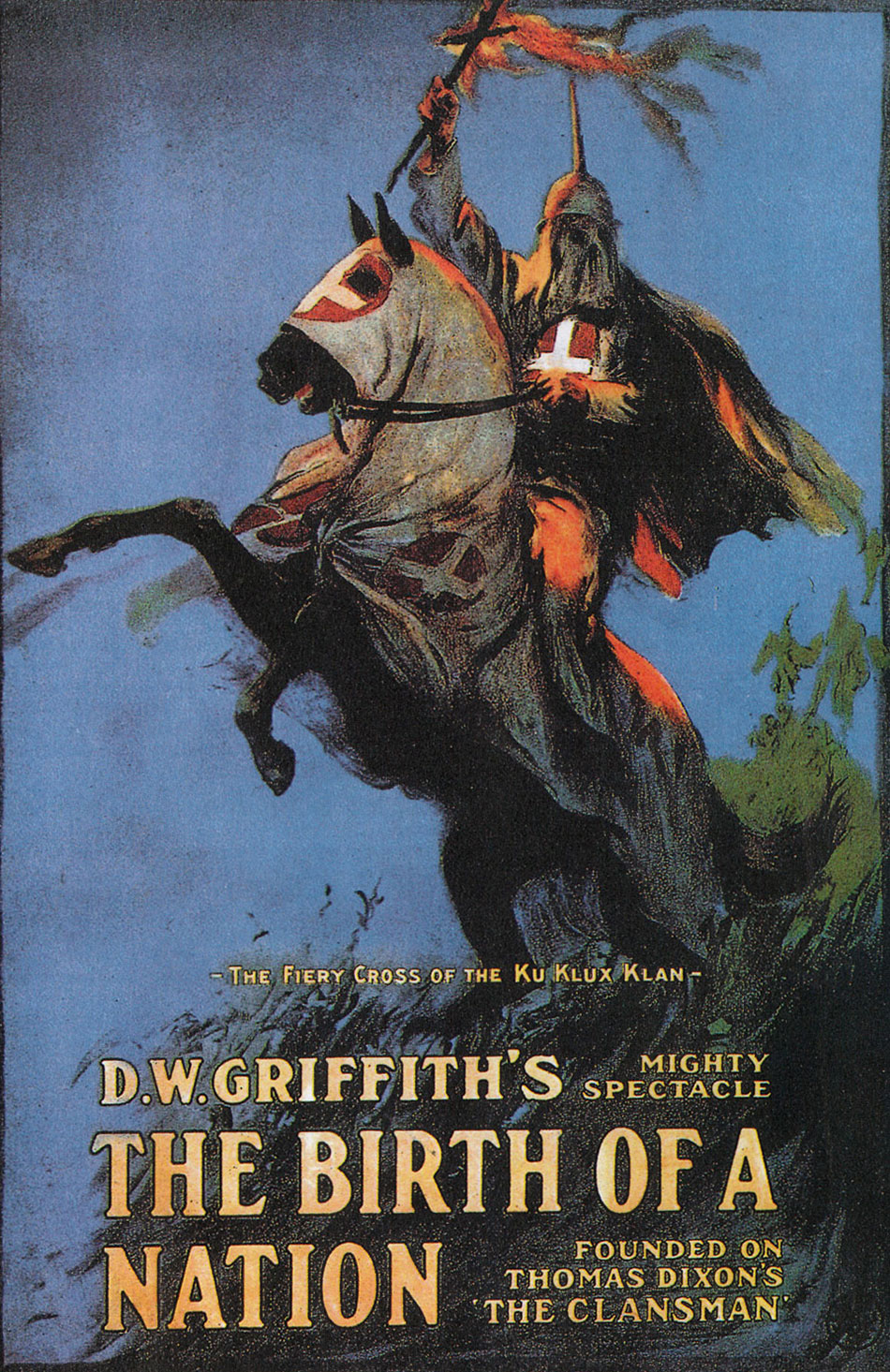

Is there value in viewing/watching films such as Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation today? Or should films so inherently racist be banned from exhibition and curricula? If not, what purpose do such films serve?

-

How have recent events such as the murders of George Floyd, Trayvon Martin, and Ahmaud Arbery solidified or challenged some of the longstanding race-based stereotypes? How have such events altered racial perceptions? And what role does media play in advancing or promoting the negative imagery?

-

Contemporary Black filmmakers such as Tyler Perry (in his Madea movies) and Spike Lee (in Bamboozled and his many other social-issue films) have used enduring racial stereotypes in order to exploit or expose them. Is this an effective approach to challenging and reversing the old stereotypes?

-

Davarian L. Baldwin, Chicago’s New Negroes: Modernity, the Great Migration, and Black Urban Life (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007).

The early twentieth-century migrations that turned Chicago into a new Black urban center created what Baldwin calls “a marketplace intellectual life” that included various Black communal and cultural institutions. Through his careful examination of early cinema and the other “consumer-based amusements” that existed alongside the more formal arenas of church and academe, Baldwin provides important new directions for historical study.

-

Donald Bogle, Toms, Coons, Mulattoes, Mammies, and Bucks: An Interpretive History of Blacks in America, 3rd ed. (New York: Continuum, 1994).

One of the classic early studies of Blacks in cinema, the volume examines Black representation and Black stereotyping in twentieth-century film. In his analysis of films from The Birth of a Nation and Gone with the Wind to recent productions by Spike Lee and John Singleton, Bogle reveals the ways in which the depiction of Blacks in American movies has (and has not) changed or evolved over the years.

-

Pearl Bowser and Louise Spence, Writing Himself into History: Oscar Micheaux, His Silent Films, and His Audiences (New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 2000).

An analysis of the first decade of Micheaux’s career, during which he produced and directed more than twenty silent features that established his reputation as American cinema’s most prolific and controversial early race filmmaker. Bowser and Spence provide a close textual analysis of the surviving films, discuss Micheaux’s novels (especially the way that they influence the films), and create a valuable social and cultural historical context that allows a fuller understanding of Micheaux and his contemporaries.

-

Pearl Bowser, Jane Gaines, and Charles Musser, eds. Oscar Micheaux and His Circle: African-American Filmmaking and Race Cinema of the Silent Era (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2001).

This immensely valuable study of Oscar Micheaux and his “circle” of fellow race filmmakers includes essays by leading film scholars. The essays examine pioneers of African American cinema and argue for the importance of their work in American cinema history. Written in a style that is accessible to general readers, the volume includes numerous illustrations as well as a helpful appendix of films by early race filmmakers such as Micheaux, the Colored Players, and Richard E. Norman.

-

Gerald R. Butters, Jr., Black Manhood on the Screen (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2002).

Concentrating on works largely ignored by many contemporary film scholars, Butters examines both African American-produced/directed films and white independent productions of all-Black features. Using these “race movies,” he explores the construction of masculine identity and the use of race in popular culture; and he separates cinematic myth from historical reality: “the myth of the Euro-American-controlled cinematic portrayal of black men versus the actual black male experience.”

-

Cara Caddoo, Envisioning Freedom: Cinema and the Building of Modern Black Life (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2014).

Viewing turn-of-the century African American history through the lens of cinema, Envisioning Freedom examines the forgotten history of early Black film exhibition during the era of mass migration and Jim Crow. As Caddoo demonstrates, African Americans emerged as pioneers of cinema from the 1890s to the 1920s. By embracing the new medium of moving pictures at the turn of the twentieth century, they forged a collective—if fraught—culture of freedom.

-

Thomas Cripps, Black Film as Genre (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1979).

An examination by one of the leading Black film historians of the history, roots, characteristics, and themes of the Black film genre and an analysis of six films including The Scar of Shame, St. Louis Blues, and Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song.

-

Thomas Cripps, Making Movies Black: The Hollywood Message Movie from World War II to the Civil Rights Era (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993).

Another of Cripps’ historical studies of African Americans in Hollywood, Making Movies Black covers the period from World War II through the civil rights movement of the 1960s. Through the prism of popular culture, it shows how movies anticipated America’s changing ideas about race and includes sixty photographs that illustrate the era.

-

Thomas Cripps, Slow Fade to Black: The Negro in American Film, 1900-1942 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1977).

A definitive history of African American accomplishment in film—both before and behind the camera—from the earliest movies through World War II. In his examination of the changing attitudes toward African Americans both in Hollywood and the nation at large, Cripps offers a perceptive social commentary on evolving racial attitudes in this country during the first four decades of the twentieth century.

-

Manthia Diawara, Black American Cinema (New York: Routledge, 1993)

A collection of essays on African American film, media, and visual culture that integrates theory, history, and criticism. Essays consider topics such as what constitutes a Black film tradition, the relationship between Black American filmmakers and filmmakers from the diaspora, the nature of Black film aesthetics, and the construction of Black sexuality on screen. Multidisciplinary methodologies encompass American studies, cinema studies, cultural studies, political science, media studies, and queer theory.

-

Anna Everett, Returning the Gaze: A Genealogy of Black Film Criticism, 1909-1949 (Durham: Duke University Press, 2001).

While much of the existing scholarship on African Americans and the cinema focuses on image studies and stereotypical representations, Everett examines the extensive and all-but-forgotten participation of Black film critics during the early twentieth century. Her work looks directly at Black newspapers, magazines, and other writings to demonstrate the significance of the early Black press, especially in raising issues such as lynching and in promoting the work of Black film entrepreneurs.

-

Allyson Nadia Field, Uplift Cinema: The Emergence of African American Film and the Possibility of Black Modernity (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2015).

Uplift Cinema recovers the significant yet forgotten legacy of African American filmmaking in the 1910s. Although none of the films survives, Field uses archival film ephemera to present a method for studying lost films and excavates the rich history of the ideological, economic, and aesthetic tensions that structured the emergence of Black American film production and exhibition.

-

Jane M. Gaines, Fire and Desire: Mixed-Race Movies in the Silent Era (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2001).

In the silent era, American cinema was defined by two separate and parallel industries, with white and Black companies producing films for their respective, segregated audiences. Gaines’ study reconsiders the race films of the era by closely examining the Black independent film movement during the period and traces the tremendous impact that D. W. Griffith’s racist epic The Birth of a Nation had on independent race filmmakers. She also questions the category of “race films” itself.

-

J. Ronald Green, Straight Lick: The Cinema of Oscar Micheaux (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000).

In Straight Lick, Green demonstrates the various strategies, both subtle and overt, that Micheaux used to counter the prevailing Black stereotypes and, especially in films such as Within Our Gates and Symbol of the Unconquered, to respond to the bitter racism of Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation. Green also explains why Micheaux, who strove for “uplift” in his pictures, refused to shy away from controversial topics such as lynching and Klan violence; and he provides close and provocative readings of Micheaux’s films.

-

J. Ronald Green, With a Crooked Stick: The Films of Oscar Micheaux (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000).

Building on his earlier study, Green analyzes Micheaux’s surviving films in detail and offers a valuable perspective on African American filmmaking and on the African American film experience of the 1920s and 1930s. Specifically, Green shows how, with a “crooked stick,” Micheaux sought to hit a “straight lick” by stressing class mobility, or “uplift,” for African Americans and how he emphasized the uplift theme in all of his films, both silent and sound.

-

Ed Guerrero, Framing Blackness (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1993).

Guerrero argues that the commercial film industry, from Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation to Spike Lee’s Malcolm X, reflects white domination of American society, and he shows how the recent Black wave of filmmakers protest negative and demeaning screen images of blacks and use their films to express their rage at social injustice. He also examines the contradiction of such imagery in his examination of roles played by stars like Sidney Poitier, Eddie Murphy, Whoopi Goldberg, and Richard Pryor.

-

Wil Haygood, Colorization: One Hundred Years of Black Films in a White World (Reel Art Press, 2021).

An encyclopedic history of Blacks’ film presence, Colorization draws on interviews as well as archival sources to tell a story of “frustrations, defiance, and bold dreams.” Highly readable and entertaining, it includes biographies of superstars such as Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte, Denzel Washington; directors Gordon Parks, Melvin Van Peebles, Jordan Peele, and Spike Lee; and actors such as Lena Horne, Diana Ross, and Cicely Tyson.

-

John Duke Kisch, The First 100 Years of Black Poster Art (Reel Art Press, 2014).

With introductions by Henry Louis Gates and Spike Lee, this beautifully and profusely illustrated volume tells the historic journey of the Black film industry in both text and images. Selected from materials in Kisch’s own “Separate Cinema Archive” collection, the posters bring surprising insights into social attitudes and give readers of all ages something to savor and enjoy. Truly a visual delight.

-

Phyllis R. Klotman, Frame by Frame: A Black Filmography (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 1979).

A classic filmography that lists over 3,000 film items with Black themes and subject matter from 1900-1977. Each entry is categorized by type, annotated, and supplemented with a complete cast list.

-

Daniel J. Leab, From Sambo to Superspade: The Black Experience in Motion Pictures (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1975).

In his classic study of Black representation on film, Leab examines familiar early stereotypes, many of them drawn from nineteenth-century minstrel shows, and reveals how they are repeated and reinforced, albeit more subtly, in later films. Leab’s discussions range from early films such as Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation through the films of the 1950s-1960s starring “Ebony Saint” Sidney Poitier and the 1970s Blaxploitation films such as Shaft and Superfly, which attempted to appropriate the stereotypes and use them against themselves.

-

Barbara Tepa Lupack, ed., Early Race Filmmaking in America (New York: Routledge, 2015).

A collection of essays by top film scholars including Jane Gaines, Linda Williams, Chris Horak, Davarian Baldwin, Allyson Nadia Field, Gerald Butters, Jr., Cara Caddoo, and others, the volume examines race filmmaking from numerous perspectives. By reanimating a critical but neglected period of early cinema—the years between the turn-of-the-century and 1930—it provides a fascinating look at the efforts of early race film pioneers and offers a valuable portrait of race and racial representation in American film and culture.

-

Barbara Tepa Lupack, Literary Adaptations in Black American Cinema: From Micheaux to Morrison, expanded ed. (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2010).

Early cinematic representations of Blacks distorted Black experience and restricted Black characters to minor and stereotypical roles. By contrast, in the works of Black writers, from Micheaux to Morrison, the Black experience has been more fully, more accurately, and usually more sympathetically realized; and from the early days of film, select filmmakers have looked to that literature as the basis for their productions. The volume offers a historical examination of the practice of such adaptation and provides telling insights into the portrayal and progress of Blacks in American movies and culture.

-

Barbara Tepa Lupack, Richard E. Norman and Race Filmmaking (Bloomington: University of Indiana Press, 2014).

Southern-born white filmmaker Richard E. Norman, who started his film career as a roving “home talent” producer and film developer, went on to produce high-quality feature-length race pictures; and, ultimately, his work would help to define early race filmmaking. This first (and, to date, only) full-length study of Norman and his films uses unique archival resources, including Norman’s personal and professional correspondence, detailed distribution records, and newly-discovered original shooting scripts in order to paint a portrait of race in early cinema.

-

Paula J. Massood, Making a Promised Land: Harlem in Twentieth-Century Photography and Film. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2013).

A fascinating examination of the interconnected histories of African American representation, urban life, and citizenship as documented in still and moving images of Harlem over the last century. Massood demonstrates how the history of photography and film in Harlem provides the keys to understanding the neighborhood’s symbolic resonance in African American and American life, especially in light of the recent urban redevelopment that has redefined many of its physical and demographic contours.

-

Peter Noble, The Negro in Films (New York: Arno Press, 1970).

A pioneering study at the time of its original publication in 1948, the volume is now rather dated and incomplete. Nonetheless, it serves as an early example of scholarship on race representation and is worth perusing if only to see how far race film scholarship has evolved over the years.

-

Lindsay Patterson, ed., Black Films and Film-Makers: A Comprehensive Anthology from Stereotype to Superhero (New York: Dodd, Mead, 1975).

A collection of twenty-nine essays on various aspects of Black cinema that survey individual films and discuss Black actors, filmmakers, and film trends. As a whole, the volume demonstrates the development and importance of Black films and considers images of Black life and characters. Contributors include Thomas Cripps, Alain Locke, Sterling Brown, Bosley Crowther, and Pauline Kael.

-

Jim Pines, Blacks in Films: A Survey of Racial Themes and Images in the American Film (London: Studio Vista/Cassell & Collier Macmillan, 1975).

Like Peter Noble’s book The Negro in Films (1948), Blacks in Films was an important study but now is quite dated. Embracing not only racial but also aesthetic concerns, Pines analyzes individual films and places them in a socio-historic context. Of special interest are his examinations of early films such as the musical Hallelujah (1929), which signaled a new interest by Hollywood filmmakers in “Negro themes” and essentially brought to a close the filmmaking efforts of most independent race film pioneers.

-

Charlene Regester, African-American Actresses: The Struggle for Visibility, 1900-1960. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010).

Regester, a prominent film historian, focuses on nine actresses, from Madame Sul-Te-Wan in The Birth of a Nation (1915) to Ethel Waters in The Member of the Wedding (1952). Regester’s discussion raises interesting questions about racial and gender politics in Hollywood and in society and about notions of white vs. Black stardom. She also reveals the sacrifices that many of these actresses were forced to make to further their careers.

-

Mark A. Reid, Redefining Black Film (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993).

Reid asks the vital question: “can films about black characters, produced by white filmmakers, be considered ‘black films’?” In answering the question, he reassesses Black film history and discusses Black independent films—defined as films that focus on the Black community and that are written, directed, produced and distributed by Blacks—ranging from the earliest turn-of-the-century efforts through the civil rights movement of the 1960s and the emergence of feminism in Black cultural production.

-

Larry Richards, African-American Films through 1959: A Comprehensive Illustrated Filmography (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Company, 1998).

Richards’ filmography details films with predominantly or entirely African American casts as well as films about African Americans. The entries include cast and credits, year of release, studio, distributor, type of film (feature, short, or documentary), and other production details, and, in many cases, offer a brief synopsis of the film or a contemporary review of it.

-

Henry T. Sampson, Blacks in Black and White: A Source Book on Back Films, 2nd ed. (Metuchen, NJ: Scarecrow Press, 1995).

An acclaimed study by one of the earliest and most distinguished scholars of Black film, Blacks in Black and White remains a seminal volume for film specialists and generalists alike. It details all aspects of a unique era in the history of motion pictures and traces the history of the Black film industry from its beginnings around 1910 to its demise in 1950 and chronicles the activities of pioneering Black filmmakers and performers who have been virtually ignored by film historians.

-

James Snead, White Screens, Black Images: Hollywood from the Dark Side (New York: Routledge, 1994).

In its exploration of racial coding in Hollywood cinema from 1915 to 1985, Snead’s study illustrates the major methods through which racial ideology functions in film: “mythification,” marking, and omission. The analysis includes both classical Hollywood and Black independent films.

-

Jacqueline Najuma Stewart, Migrating to the Movies: Cinema and Black Urban Modernity (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005).

The rise of cinema around the turn of the last century coincided with the migration of hundreds of thousands of African Americans from the South to the urban “land of hope” in the North. Stewart’s landmark volume offers an excellent and thorough examination of the early relationships between African Americans and the cinema by exploring African American migrations on the screen, into the audience, and behind the camera; and it shows how African American urban populations shaped cinema and vice-versa.

-

Linda A. Williams, Playing the Race Car: Melodramas of Black and White from Uncle Tom to O.J. Simpson (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002.

Williams examines how certain familiar images—such as Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom and Griffith’s endangered women in The Birth of a Nation—became part of the American conscience and popular culture. She discusses how these images took root, beginning with melodrama in the theater, where suffering characters acquired virtue through their victimization, and she traces the development of Black and white racial melodrama through stage, screen, and television.

-

Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1910 / re-release 1927, Vitagraph version) – YouTube

-

Uncle Tom’s Cabin (Sam Lucas, Walter Hitchcock, Hattie Delaro, 1914) – YouTube

-

Uncle Tom’s “Uncle Tom,” a compilation of racist images and cartoons – YouTube (Note: this video contains stereotypes that some people may find racially offensive.)