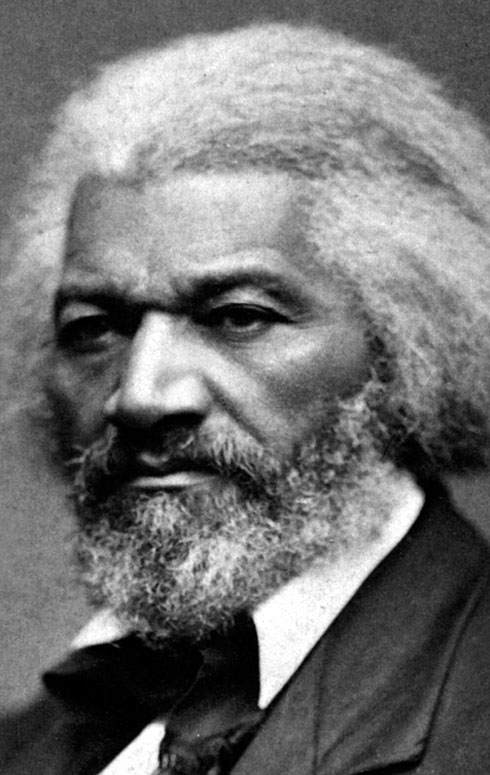

FREDERICK DOUGLASS FILM COMPANY

The company’s first production, The Colored American Winning His Suit (1917), aimed, according to the press book, “to offset the evil effects of certain photo plays that have libeled the Negro and criticized his friends; to bring about a better and more friendly understanding between the white and colored races; to inspire in the Negro a desire to climb higher in good citizenship, business, education and religion.”[2] The film, whose screenplay was written by Reverend Dr. W. S. Smith, was a kind of modern morality play: young Bob Winall (Thomas M. Mosley), a humbly born young black man who graduates from Howard University and becomes a lawyer, must fight various obstacles to win the hand of Alma Elton (Ida Askins), the woman he loves.

In court, he is forced to go up against a white man, Mr. Hinderus (F. King), in order to defend Alma’s father against a charge of theft; and with the help of Colonel Goodwill (Fred Leighton), he prevails. The white man’s attempt to “hinderus” having failed, Winall—through “goodwill”—indeed wins all. The New York Age (July 20, 1916) hailed the film as “the first five-reel Film Drama written, directed, acted and produced by Negroes” and praised the company, which was “owned and operated by Negroes” and “whose aim is to present the better side of Negro life, and to use the screen as a means of bringing about better feeling between races.”[3][4]

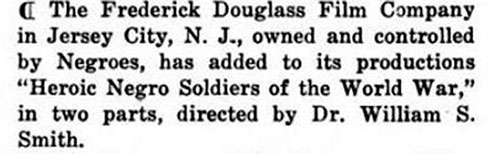

Announcement in The Crisis, October, 1919

Told in three parts, the film lacked “a certain cohesiveness of sequence” and the characters at times were “thrust into new environments and new conditions with startling abruptness.” Moreover, the doctors, ministers, and other “race representatives [who] are supposed to be classed among the ‘intellectuals’ of the race” were forced to speak in the dialect that “seem[ed] to be the rage among writers of dramas and photoplays.”[5] Nevertheless, the film appealed to its audiences in both the “white and colored motion picture houses” in which it was booked. Like so many other black film companies, however, the Douglass Company struggled to develop appropriate outlets for the distribution of its films, while lack of capital stalled plans for new projects. The company released its final production, Heroic Negro Soldiers of the World War, in March, 1919. A pictorial demonstration of the bravery of black soldiers,—including the “Black Devils,” the “Hell Fighters,” the “Buffaloes,” and the “Red Devils,”—in action under fire in France, it was considered the best documentary film yet produced.