X …is for

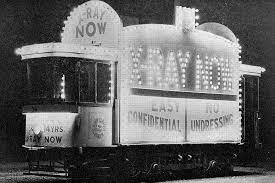

The X-Rays

Although it ran a mere forty-four seconds long, The X-Rays told a curious story of two Victorian-era lovers (played by Tom Green and Laura Bayley, the wife of the film’s British director George Albert Smith), who are courting on a park bench. A mysterious man appears, holding in his hand a machine emblazoned with the word “X-Rays.” That machine, which he trains on the pair, instantly transforms them into bony skeletons and even exposes the ribs of the woman’s umbrella. After the man departs, the lovers resume their original form and begin to quarrel. Rebuffing her beau’s advances, the woman walks away, leaving him alone and disgruntled.

Like Méliès, Smith had performed on stage before turning his talents to film. A skilled hypnotist, psychic, and inventor, he became a key member of the loose association of early cinema pioneers dubbed the Brighton School by French film historian Georges Sadoul. A technical innovator renowned for his clever special effects, he was among the earliest filmmakers to employ close-ups, pan shots, iris effects, jump cuts, and double exposure. He also developed an early and promising color film process, Kinemacolor; but legal battles and lawsuits ultimately drove him out of business.

Throughout his brief and now largely forgotten film career, Smith produced numerous influential short pictures, including the landmark A Kiss in the Tunnel (1899), in which a couple shares a kiss as their train passes through a tunnel—a picture that is said to mark the beginning of narrative editing and the creation of the grammar of filmmaking. Let Me Dream Again (1900) employed a cross-fade to contrast dream and reality, as a man flirts happily with a lovely young woman but then wakes up next to the frumpy, short-tempered wife lying in bed beside him. And in Mary Jane’s Mishaps (1903), the eponymous housemaid (played by Laura Bayley) uses paraffin to light a fire, inadvertently sends herself through the chimney of her home, and is buried below a gravestone where she “rest[s] in pieces.” The illusion film cleverly used “wipe” scenes and superimposition to “resurrect” Mary Jane’s ghost.

A number of elements and techniques that Smith employed in his trick films (“trick novelties,” in British parlance) became a vital part of early silent film and serial history and practice. In the final episode of the Wharton Brothers’ The Exploits of Elaine, for example, Dr. Craig Kennedy uses an X-ray machine to detect and dismantle a bomb and to expose the villainous Clutching Hand. And numerous other silent serials—Zudora (1914), The Shielding Shadow (1916), The Yellow Menace (1916), The Great Radium Mystery (1919), The Flaming Disc (1920), The Power God (1920), The Scarlet Streak (1925), among them—featured various forms of radiomagnetic radiation, including the ever-popular death ray, a staple of many early action pictures.

Survival Status: A print exists at the National Film and Television Archive of the British Film Institute. Access at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3gMCkFRMJQQ. (Le Squelette joyeux [1898], A Kiss in the Tunnel [1899], Let Me Dream Again [1900], and Mary Jane’s Mishap [1903] are also extant and available for viewing on YouTube).

Director: George Albert Smith

Release Date: October, 1897

Release Company: George Albert Smith Films

Cast: Tom Green, Laura Bayley