NOBLE AND GEORGE JOHNSON

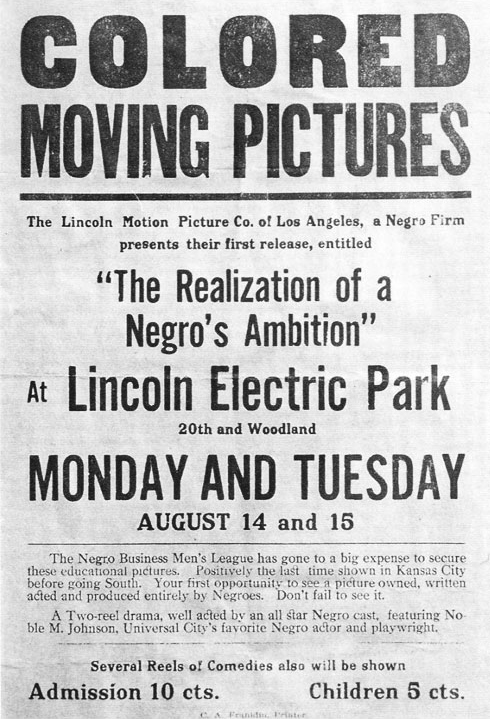

The Lincoln Motion Picture Company

The first feature film by the Johnson Brothers emphasized black ambition and uplift.

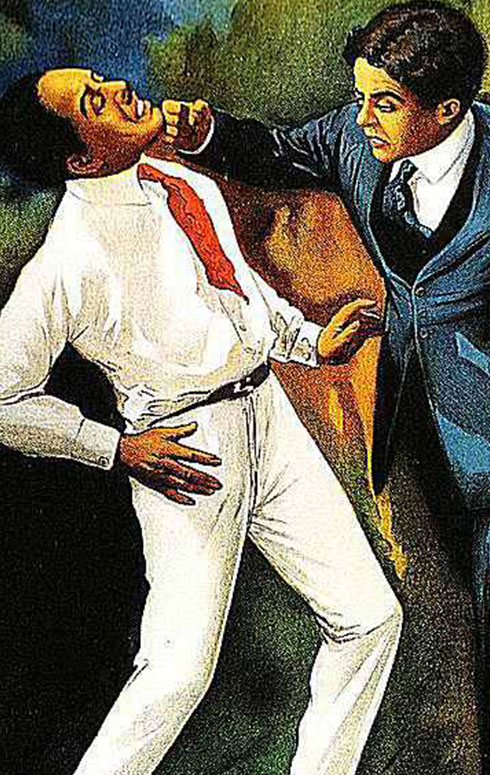

Another Lincoln film, The Law of Nature (1917), soon followed. In that film, which again starred Noble Johnson and included Albertine Pickens, Clarence Brooks, Estelle Everett, Stebeno Clements, Frank White, Elsworth Saunders, and Sallie Richardson in the cast, a woman leaves her rancher husband and children to revisit the glamorous East of her former days; but she soon finds herself humiliated, alone, and ill. Realizing her folly and the inevitable consequences of her violation of “Nature’s Law,” she returns west to rejoin her family. Like the company’s earlier productions, The Law of Nature proved to be “a fine story,” “an artistic and well portrayed success,” and a “good box-office attraction”[6]. An ad for the Omaha run described it as a “classy” and uplifting picture with “a wholesome moral”[7]. The manager of the Palace, a black-owned, black-managed theater in Louisville, Kentucky, wrote to George Johnson that The Law of Nature “took on like wild fire.” Even the white-owned, white-managed Alamo Theater in Washington, D.C., listed the film as the “biggest drawing card” of all of Lincoln’s productions[8].

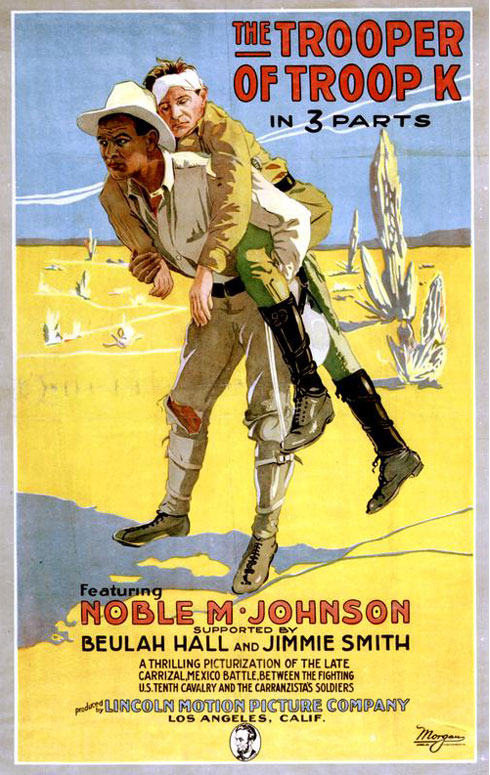

Lincoln’s fortunes changed, however, with the resignation of Noble Johnson in 1918. The Universal Picture Company of Hollywood, which employed Johnson as a featured player, had exerted pressure on him to step down from his responsibilities at Lincoln. In fact, it was a condition of Johnson’s contract with Universal that he sever his ties with the company he founded and that Lincoln be prohibited from using Johnson’s name or likeness in new advertising; similarly, Lincoln could not utilize existing advertising in new ways, including “any part of the negative or positive films, slides, stills, plates, cuts, heralds, or lithographs”[9]. The minutes of the September 3 company meeting recorded that Johnson tendered his resignation because he could no longer devote the necessary attention to company business and indeed requested, as Universal insisted, that the company no longer use his name in association with new productions or products[10]. Such a repressive and cutthroat demand was no doubt precipitated by Johnson’s immense popularity as an actor: the multi-talented Johnson, who had appeared in more than thirty films between 1915 and 1918, was such a box-office draw in the black community that black audiences would readily turn out for the white studio pictures in which he was featured. Ironically, therefore, Johnson’s very popularity spelled doom for his own fledgling black company, which Universal perceived as potentially serious competition for their productions[11].

After Noble Johnson’s departure, the company turned for leadership to his brother, former newspaper and real-estate man George P. Johnson. George accepted the position of Lincoln’s General Booking Manager but insisted that he be allowed to work from Omaha, Nebraska, so that he could keep his job as the first Negro clerk in the U.S. Post Office. George soon forged a number of strong alliances for Lincoln, most notably with Tony Langston, the influential theatrical editor of the Chicago Defender, which publicized the company’s films, and Romeo Daugherty, an editor at the New York Amsterdam News; opened several branch offices; employed advance men to promote Lincoln’s features at smaller theaters; and, perhaps most importantly, established the first black-operated national booking organization to increase and facilitate the distribution of its race films[13].

During George’s tenure, the company released A Man’s Duty (1919), a story of conflict between a man’s moral obligation and his newfound happiness, with Clarence Brooks in the lead role that was originally meant to be Noble Johnson’s, and By Right of Birth (1921), another picture of race achievement in which slavery is reversed and negated by a legacy of wealth for succeeding generations, with Clarence Brooks and Anita Thompson starring in a screenplay written by George Johnson himself. (Interestingly, in an early example of a movie tie-in, with the help of Robert L. Vann, the publisher of the Pittsburgh Courier, Johnson published a novelization of A Man’s Duty in Vann’s magazine, The Competitor[14].) Plans for a new production, The Heart of a Negro, featuring Clarence Brooks, Edna Morton, and Lawrence Chenault, were announced in 1923; but the film was never produced.