Race Women and Uplift: The Colored Players Film Corporation

by Ken Fox

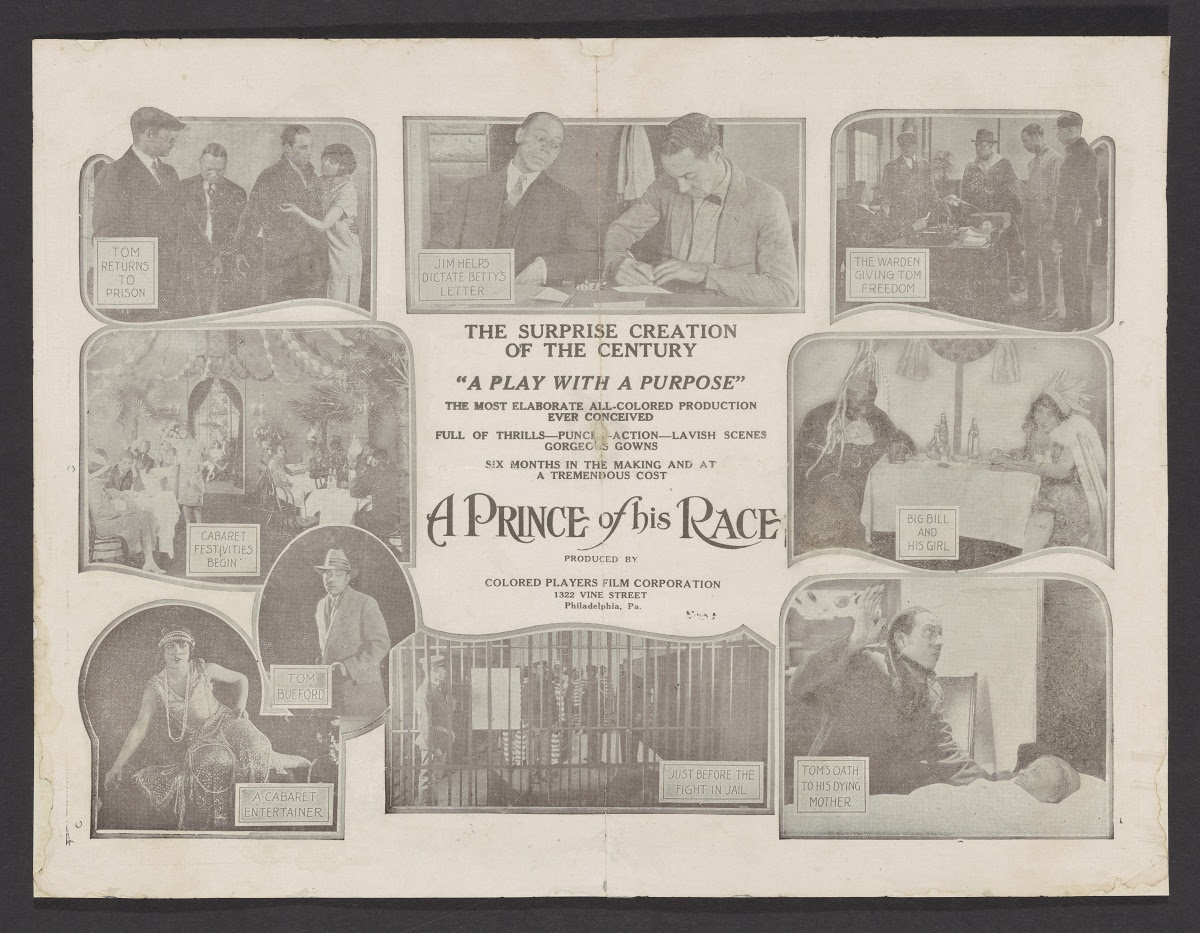

By the early 1920s, numerous independent companies had entered the race film industry, albeit with mixed results. Some, like Ebony, merely perpetuated the degrading stereotypes, while others, despite their ambition, failed to produce even a single film before going out of business. One of the best and most successful of the silent race film companies, though, was the Colored Players Film Corporation of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, co-founded by White entrepreneur and theater owner David Starkman and popular Black stage performer and Vaudevillian Sherman H. Dudley. Although Dudley was the titular president of the company, it was actually Starkman who was in charge of its operation, management, and finances; and it was money from White backers that funded the films that the company produced.

Ten Nights in a Bar-Room (1926)

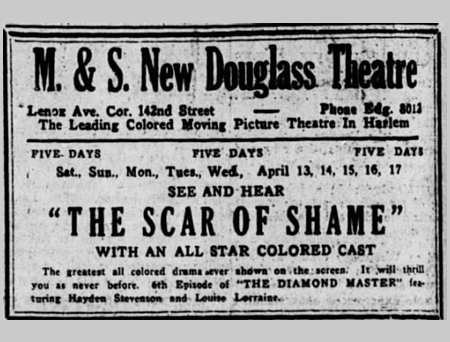

Figures of race pride and power, women in race films such as The Scar of Shame were the embodiment of uplift and ambition.

The Colored Players Film Corporation distinguished itself from other race film companies in several ways, including its expensive sets and its cadre of prominent Black actors such as Lawrence Chenault, Harry Henderson, and Shingzie Howard. Of the four pictures that the company produced, two are extant. Ten Nights in a Barroom (1926) was a Black version of the familiar temperance novel Ten Nights in a Bar-Room, And What I Saw There (1854) by Timothy Shay Arthur, later adapted as a stage melodrama by William W. Pratt and as several White film versions, including a 1921 feature directed by Oscar Apfel. The Colored Players’ Black-cast film version, though, was particularly poignant, especially in the plea it made to avoid “urban” vices that led to ruin.

The Scar of Shame (1929)

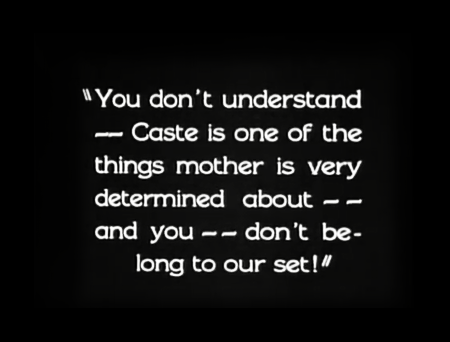

The second extant film (the company’s final film) was The Scar of Shame (1929), the story of an ill-fated marriage between the middle-class and well-educated composer Alvin Hillyard (Harry Henderson) and Louise Howard (Lucia Lynn Moses), a young woman employed in Mrs. Green’s “select” boarding house, where Hillyard lives. The film, which revealed the caste divisions that existed even among Black Americans, was quite sophisticated for its time. Using interesting intercutting of scenes to contrast the women in Alvin’s life (his wealthy mother, his wife Louise, and the proper Alice whom he meets and falls in love with after leaving Louise) and recurring symbols and leitmotifs that defined and identified the main characters, it offered a powerful commentary on race relations and on racial uplift. It is now considered to be one of the finest films of it its day, Black or White.