OSCAR MICHEAUX (1884-1951)

Micheaux Film Corporation

Oscar Micheaux

Micheaux’s films were not technically brilliant. Often forced to work on a very tight budget, Micheaux would shoot in empty and outdated studios in Chicago, Fort Lee, and the Bronx or in the houses and offices of his acquaintances.

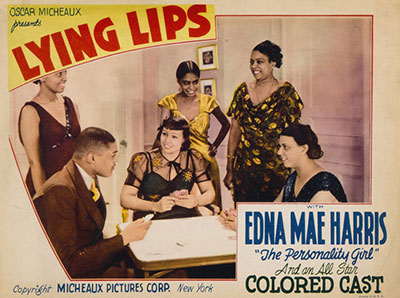

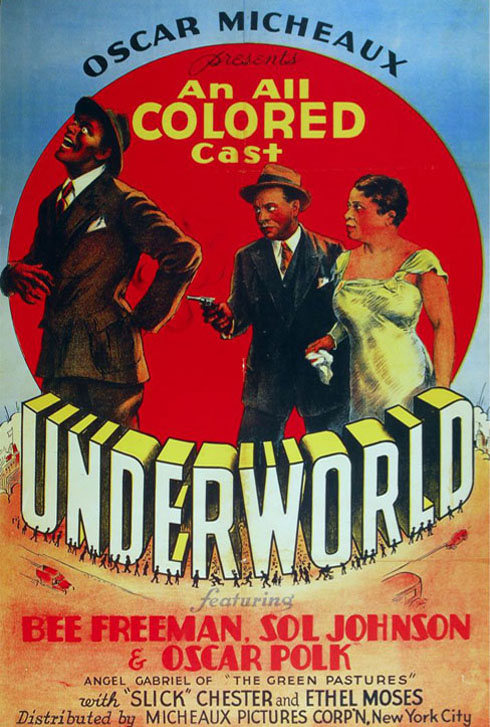

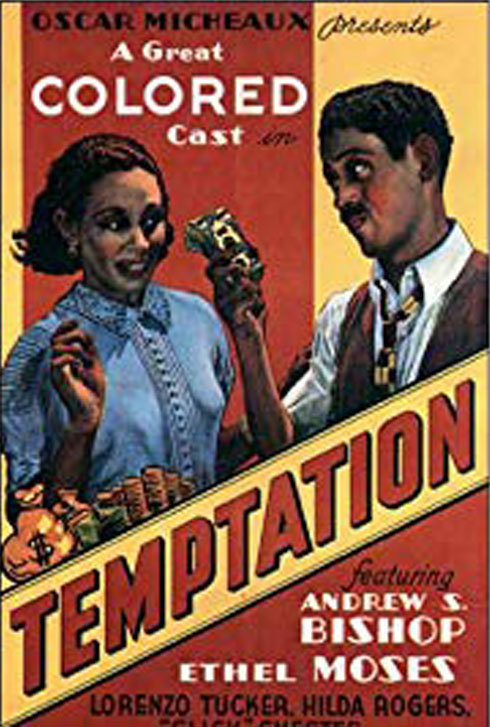

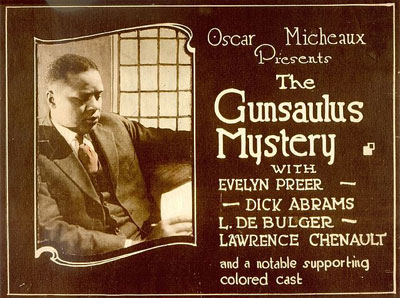

Early on in his production career, Micheaux established a cadre of performers, many of them gathered from prestigious black acting companies such as the Lafayette Players in New York, whom he would cast by type, model after white Hollywood performers in order to boost their box office appeal, and promote accordingly. The handsome Lorenzo Tucker was first referred to as the “black Valentino”; later, after “talkies” became popular, he was the “colored William Powell.” Sexy and insolent Bea Freeman was the “sepia Mae West.” The character actor Alfred “Slick” Chester, who often played gangster roles, was the “colored Cagney.” And the lovely light-skinned actress Ethel Moses was sometimes publicized as the “Negro Harlow”.[7] Evelyn Preer, who first appeared on screen in The Homesteader (1919), went on to play key roles in numerous other Micheaux films and became the most famous black female star of the 1920s but died an untimely death in 1932. Lawrence Chenault, who was the first leading man with the then newly formed Lafayette Players Stock Company, became one of Micheaux’s favorite actors after he appeared in The Brute (1920), the third film released by the Micheaux Film Corporation; eventually Chenault played more leading roles than any other performer in black pictures during the silent film era. Paul Robeson, a young football player, singer, and budding actor, made his film debut in Body and Soul (1924) in the dual roles of the greedy and licentious preacher Reverend Jenkins and his conscientious, responsible brother Sylvester. Among the other notable players whom Micheaux sought out were the boxer and celebrity Sam Langford, whom he starred in the fight scene of The Brute; the fine character actor Juano Hernandez, who appeared in Lying Lips and The Notorious Elinor Lee and who later received an Academy Award nomination for his sensitive portrayal of Lucas Beauchamp in a non-Micheaux film, Intruder in the Dust; and Oscar Polk, who was featured in Underworld but is best remembered for his roles as Scarlett O’Hara’s servant in Gone With the Wind and in other major Hollywood films such as The Green Pastures and Cabin in the Sky.

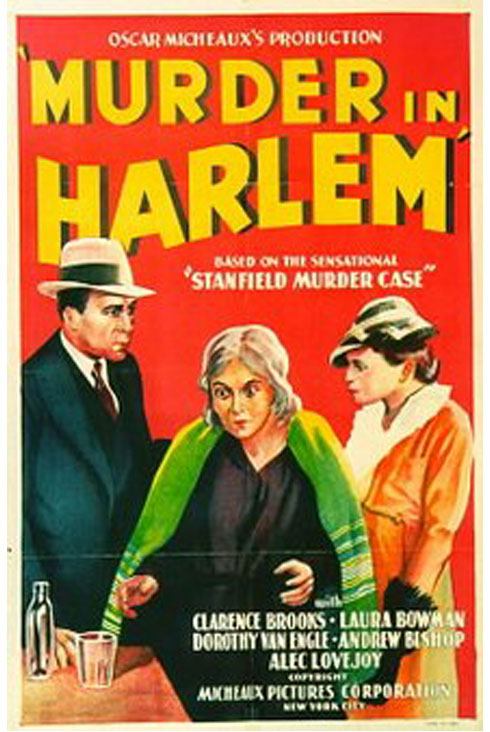

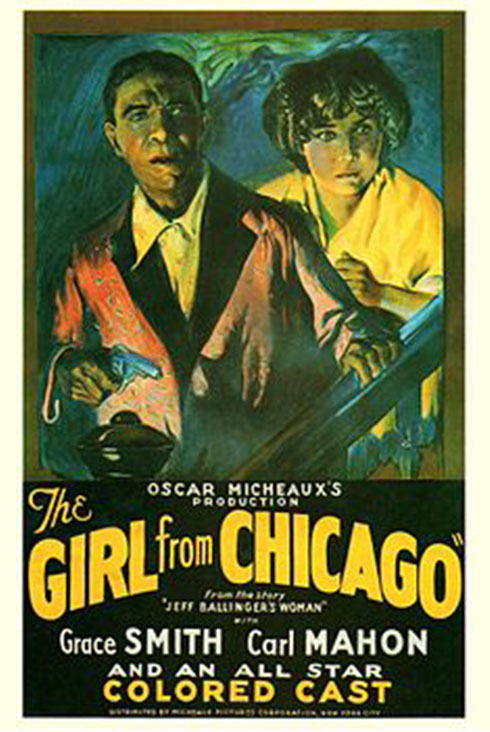

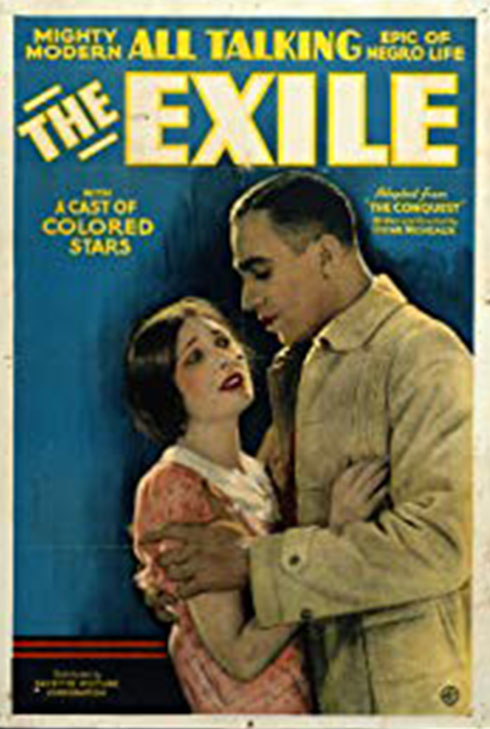

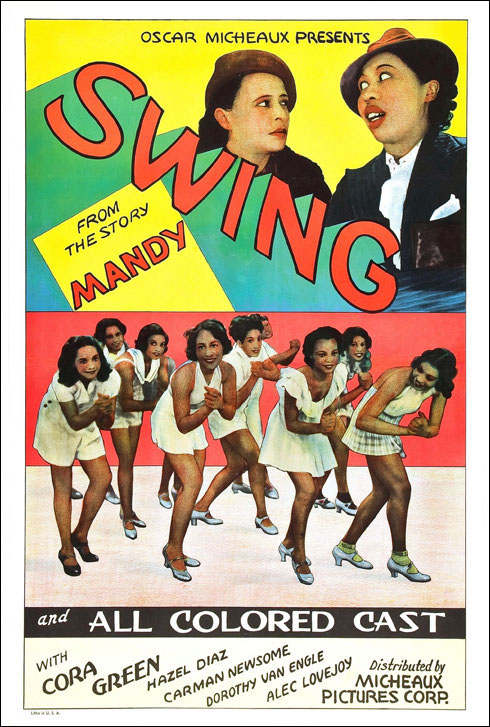

Even more than the technical aspects of filmmaking, most of which he learned on his own, Micheaux understood the art of self-promotion. He acquired that skill from marketing his own novels, usually door to door, among the white farmers of the prairie where he had lived as a young black pioneer and in the black communities of the South that he would visit. And he applied that same skill to the underwriting, promotion, and distribution of his films. To finance his productions, he would personally call upon theater managers to offer them first rights to his works; often he would bring along several cast members to act out scenes that he was planning to shoot. Once a film was completed, Micheaux would carry stills to the theaters where his features were scheduled to play and try to get advance bookings for his next film. To increase box office receipts, he scheduled promotional junkets and encouraged his stars to make personal appearances in the cities where his films were opening—a gimmick that many of the actors appreciated, since the extra publicity enhanced the stage careers that often constituted their principal livelihood. And the provocative, teasing one-sheet lithographs and theater lobby cards that Micheaux designed himself were among the most colorful and artistic in the business.[8]

Micheaux also traveled widely on behalf of his company, adapting his approach to the particular audience he happened to be addressing. At black church meetings and community functions, he would extol the merits of his race films and highlight the ways that they managed to “uplift the Negro.” With Southern whites, he would speak of the untapped black market and suggest that there were huge profits to be made by subsidizing his productions. To attract crowds of all colors to his movies, he would schedule special matinées or late-night showings; and he even hand-delivered the prints to the theaters himself.

In person, Micheaux had a distinctly theatrical flair. Actor Lorenzo Tucker recalls that Micheaux “was so impressive and so charming that he could talk the shirt off your back.”[9] Tall and solidly built at “over 300 pounds,” Micheaux often appeared in public in long Russian fur coats and wide-brimmed hats, no matter the season. Later in his career, when he was living in New York, he would drive “in a 16-cylinder car with a white chauffeur” to Chicago, where—as a colleague reported in 1940—“two-thirds of the movie houses in the Negro district of Chicago continuously show ‘Oscar Micheaux production [sic]’”.[10] His success at creating an image and his mastery of other similar kinds of tricks of the trade were, in fact, essential to his longevity. Like so many other black independents, Micheaux’s film corporation was perpetually underfinanced, and it was by the sheer force of Micheaux’s personality and his tireless and aggressive self-promotion that he was able to survive through almost three decades of filmmaking. Although he experienced a variety of financial setbacks, reorganizations, and even bankruptcies, most notably a voluntary bankruptcy in early 1928 precipitated by the mismanagement of the company by his brother Swan, Micheaux endured. Even in the 1930s, when he was increasingly forced to seek backing from white theater owners and white financiers (sometimes called “angels”) like Frank Schiffman and Jack Goldberg, he continued to exercise strict control over his projects.

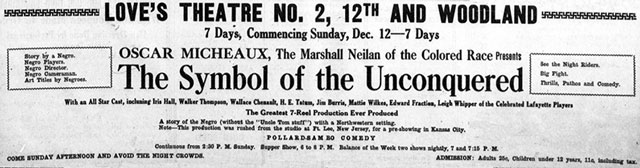

Above all, Micheaux seemed to understand his audience. Unlike many of the black companies that produced simple race films, Micheaux felt that moviegoers were more interested in good story lines than in blatant racial propaganda. “The first thing to be considered in the production of a photo-play,” he wrote, “is the story. Unfortunately, in so far as the race efforts along this line have been concerned, this appears to have been regarded as a negligible part.”[11] So Micheaux offered his viewers engaging characters with whom they could identify and popular plots that incorporated elements generally ignored by other filmmakers: lynching, race purity, prostitution, underworld crime. Intertwined in—and underlying—all of Micheaux’s films was a definite racial, even politically activist, theme, usually drawn from topical and often controversial events. In The Symbol of the Unconquered (1920), for instance, one of several films that Micheaux produced as a black response to Griffith’s The Birth of a Nation, the Ku Klux Klan, at the instigation of white racist ex-Southerner Tom Cutschawl (Edward E. King) and Jefferson Driscoll (Lawrence Chenault), a light-skinned black man who hates his own race and is passing for white, attack black rancher Hugh Van Allen (Walker Thompson) and attempt to drive him off his oil-rich property. And in Birthright (1924/1925), restrictive racial covenants prevent Harvard graduate Peter Siner (J. Homer Tutt) from building a school that might ameliorate the conditions of impoverished and undereducated blacks in his community. As Thomas Cripps observed, movies gave Micheaux the power to say, however amateurishly, “what no other Negro filmmakers even thought of saying. He filmed the unnameable, arcane, disturbing things that set black against black. When others sought only uplifting and positive images, Micheaux searched for ironies.”[12] Black novelist and cultural critic bell hooks offered a similar analysis: calling Micheaux’s screen images disruptive, she suggested that they challenged conventional racist representations of blackness. According to hooks, by being less concerned with the creation of “positive” images than with the creation of images that would convey complexity of experience and feeling, Micheaux delineated “a politics of pleasure and danger.”[13]

The midnight ride scene from The Symbol of the Unconquered

Yet while he was as much a pioneer in the film industry as he had been in real life, Micheaux was not without his detractors. Some were critical of Micheaux for using light-skinned blacks, especially light-skinned women (called “light-brights” or “high-yellows”), a practice that seemed to promote a caste system that discriminated between light and dark blacks. Black critic Theophilus Lewis, for instance, in the New York Amsterdam News, decried Micheaux’s “intraracial color fetishism” and argued that he made “artificial associations of nobility with lightness and villainy with blackness”; and in 1938, the Communist Party, which picketed the showing of God’s Step Children at Harlem’s RKO theater, objected that the film “slandered Negroes” by suggesting that “all light Negroes hate their darker brethren.[14][15] Others charged that Micheaux’s characters were not typical of black society, that they were simply darker versions of white society. Micheaux’s depiction of a black bourgeoisie, they claimed, ignored the interests and outlooks of ghettoized blacks, whose lives were replete with racial misery and decay, in favor of almost unrealistic black professionals. Conversely, still others criticized Micheaux for his grimly realistic and unflattering portraits of the black underclass, which included gamblers, alcoholics, loose women, hustlers, and other unsavory types; and they suggested that by portraying black characters in such a poor light, he was guilty of race hatred and of reinforcing the stereotypes perpetuated by whites. “What excuse can a man of our Race make when he paints us as rapists of our own women? Must we sit and look at a production that refers to us as n—-rs?” wondered William Henry, a reviewer for the Chicago Defender (January 22, 1927). And a theatergoer writing to the Baltimore Afro-American (May 5, 1928) blasted Micheaux’s productions for being so “suggestive of immoral and degraded habits” and for featuring “only the wors[t] conditions of our race and the worst language” with “no attempt whatever to portray the higher Negro as he really is.”[16]

In fact, while Micheaux did indeed employ a large number of light-skinned actors (as other black filmmakers did), he also used dark-skinned blacks in his many productions and imbued them with the same qualities of beauty and goodness, like the industrious Jimmy Saunders in God’s Step Children and the faithful, striving Frank Fowler in The House Behind the Cedars and Veiled Aristocrats. Light-skinned actor Lorenzo Tucker, who appeared frequently in Micheaux’s sound films, confirmed Micheaux’s willingness to cast against type and stereotype; and he recalled that Micheaux employed “all the shades of the black race.”[17] Moreover, Micheaux himself criticized the color-caste system within the community as destructive social behavior.[18]

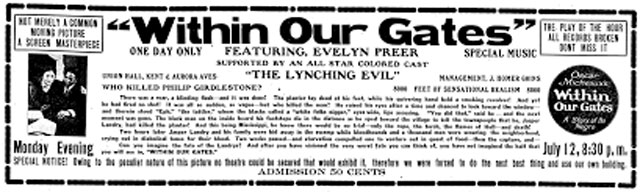

Over the years, Micheaux also had numerous problems with the censors, usually because of the explicitness of his films. Within Our Gates (1920) was originally rejected (and ultimately censured) by the Chicago Board of Censors, who feared that its graphic rape/incest scene would shock viewers’ sensibilities and its explosive lynching scenes might provoke race riots, particularly after the racial uprisings during the summer of 1919, which James Weldon Johnson termed the “Red Summer.” Even on the day that Within Our Gates opened (to a packed house), a committee of whites and blacks from Chicago’s Methodist Episcopal Ministers’ Alliance was putting pressure on the Mayor and the Chief of Police to prevent the showing. Many of the white theaters in the South that catered to black patrons on a segregated basis refused to book the film because of its “nasty” story; several white managers of black theaters in Louisiana also banned the film.[19] The controversy, however, did not deter Micheaux from subsequently restoring the footage that censors insisted on cutting or from including a lynching scene in another picture, The Gunsaulus Mystery (1921), that he based on a 1915 Georgia murder case in which a white man named Leo M. Frank was convicted of killing Mary Phagan, a young white woman, and later lynched. As Henry T. Sampson writes, “Micheaux hoped that the large coverage this case was given in the white and black press would guarantee good business at the box office. The black press also made the point that a newsreel film showing Frank’s body had been barred because it would have been objectionable to the Jewish community, but Birth of a Nation was still being shown, over protests by the black community.”[20]

The controversial attempted rape scene from Within Our Gates

Micheaux’s problems with censors, as recent scholarship has revealed, continued throughout his career. The Dungeon (1922), for instance, was disapproved for exhibition in New York State “on the basis that it was inhuman, immoral, and would tend to incite crime”; in particular, the censors seemed disturbed by the portrayals of a woman being exploited by a man and enticed by a drug fiend.[21] (Those same censors, however, failed to remark on the film’s important subplot involving political hypocrisy, in which a corrupt black politician works against the interest of his people in order to be elected to Congress.) Body and Soul required rather radical editing before it received approval in New York: Micheaux ultimately reduced the film from nine reels to five, added new title cards, and altered the theme by deflecting some of the villainy of the minister to other characters.

A controversial scene from Body and Soul

White censors in New York, in fact, insisted on changes in many of the early films, including The Virgin of the Seminole (1923), Birthright (1924/1925), A Son of Satan (1924), The Spider’s Web (1926), and The Millionaire (1927); and, ironically, they initially withheld approval of Deceit (1921), a film based on the problems that Micheaux had experienced with film censor boards over his first production, The Homesteader (1919). A Son of Satan (1924), whose plot involved an overnight stay in a haunted house, included an inflammatory protest scene of a race riot that Virginia censors insisted be cut because they feared that the film would incite “ill-feeling” among black audience members; Wages of Sin (1928), a tragic story of two brothers, one of whom cheats and steals from the other, was temporarily banned by the Chicago Board of Censors. As late as 1938, members of the Young Communist League and the National Negro Congress halted a showing of God’s Step Children (1938) at the RKO Regent Theatre in New York City: the picketers objected to the “false” division of blacks into light and dark groups and argued that the film was slanderous in “holding them [Negroes] up to ridicule.”[22]

Micheaux would prove to be the only one of the early race filmmakers to survive the transition to sound. During the decade of the 1930s, he produced numerous pictures. By 1940, however, financial problems made it impossible for him to continue his filmmaking, so he returned to the career that had initially brought him such success: the writing of fiction. Between 1944 and 1947, he completed four new novels that he self-published through a new company he founded, the Book Supply Company of New York.

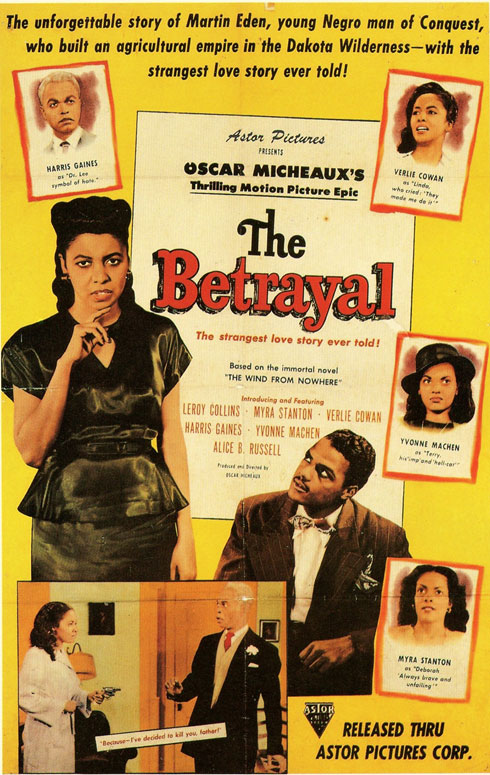

Micheaux returned briefly to filmmaking again in 1948, with his last film, The Betrayal, based on his novel The Wind from Nowhere (1941), which was another version of his familiar homesteader story. But the film, with a running time of more than three hours, was not the career-reviving success that Micheaux hoped it would be. Outdated in its themes and conventions, it was, in fact, quite possibly his biggest failure. Production costs exceeded $100,000, a significant portion of which Micheaux had personally invested. The financial loss was so severe that he never fully recovered; and he was forced to get back on the road to sell his books. In 1951, on one of those trips, he fell ill and died.

Although his work was neglected for many years and many of his films were lost, Micheaux is now recognized as one of the great early race filmmakers. In 1986, in a special ceremony in Hollywood, he was posthumously awarded a Lifetime Achievement Award by the Directors Guild of America; he was the first black filmmaker to receive the honor. Soon afterwards, a prestigious award given to black artists and filmmakers by the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame was named for him, and he was also given a star on Hollywood’s Walk of Fame. In recent years, with the rediscovery of several of his early films, Micheaux and his work have become the focus of increasing scholarly attention, as evidenced by the numerous conferences, symposiums, and film festivals convened and critical books issued of late. Several important new studies were published in 2000 and 2001 alone: Pearl Bowser and Louise Spence’s Writing Himself into History: Oscar Micheaux, His Silent Films, and His Audiences; Jane M. Gaines’ Fire and Desire: Mixed-Race Movies in the Silent Era; J. Ronald Green’s Straight Lick: The Cinema of Oscar Micheaux; and Oscar Micheaux and His Circle: African-American Filmmaking and Race Cinema of the Silent Era, edited by Pearl Bowser, Jane Gaines, and Charles Musser. And the interest in Micheaux continues, with books written or edited by J. Ronald Green Patrick McGilligan, Earl James Young, Jr., and Betty Carol Van Epps-Taylor, among others.