REOL PRODUCTIONS

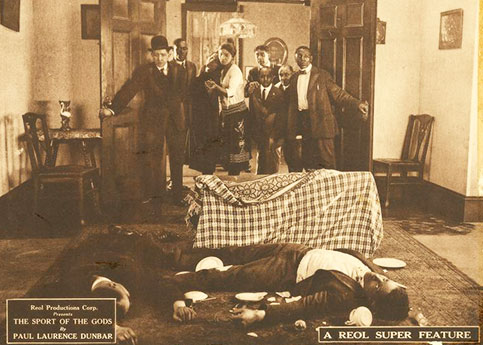

The film’s ending is thus more upbeat than the novel’s, in which Berry and Fannie—having nowhere else to go—return to their cottage on the Oakley property. “It was not a happy life,” Dunbar writes in the novel, “but it was all that was left to them, and they took it up without complaint, for they knew they were powerless against some Will infinitely stronger than their own.” As the reviewer for the California Eagle (July 30, 1921) noted, “the thrilling movie taken from Paul Laurence Dunbar’s beautiful Folk Poetry . . . depicts the highest type of Negro life [in the opening scenes], and very cleverly points out the fine points of the relationship between the two Races from a Southern viewpoint.”

Another early Reol film was The Call of His People (1922), which was advertised as an adaptation of “The Man Who Would Be White,” the “famous story” by black writer Aubrey Bowser about a black who is light enough to pass for white. Passing, or racial duplicity, was a popular theme among black writers and filmmakers, who employed it as a way to explore the meaning of race pride and sometimes, more subversively, to refute white misconceptions about black characteristics and capabilities as well as white attempts to create racially pure cultural spaces.[3] According to Donald Bogle, like other passing films, The Call of His People “seemed to be the wish-fulfillment yearnings” of its producers, and it “revealed the preoccupation of black America at the time: how to come as close as possible to the great White American Norm.”[4] The film ran six reels and included in its cast Lawrence Chenault, the popular actor who also starred in several of Oscar Micheaux’s films, along with Edna Morton, George Brown, Mae Kemp, James Stevens, Mercedes Gilbert, and Percy Verwayen.

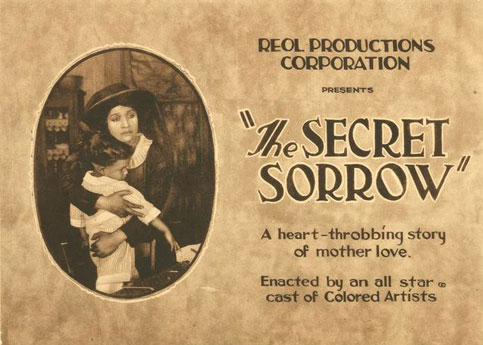

In addition to the films it adapted from works by Dunbar, Bowser, and Brown, Reol planned to bring to the screen Charles W. Chesnutt’s The Marrow of Tradition, although there is no record that the film was ever completed or released.[7] Before going out of business in 1924, however, Reol produced at least ten feature films that were notable both for their high quality and for the lack of stereotyping of the black characters. Yet, despite Reol’s success in black theaters, Levy was disappointed that he did not get more support and encouragement from the black community—a sentiment shared by many black filmmakers. An article in the Baltimore Afro-American (May 2, 1924) quoted Levy as saying: “Negro amusement buyers are fickle and possessed of a peculiar psychic complex, and they prefer to patronize the galleries of white theatres than theirs.” Levy’s sentiments seemed only to confirm William Foster’s earlier fears that whites would inevitably “step in and grab off another rich commercial plum from what should be one of our own particular trees of desirable profit.”[8]