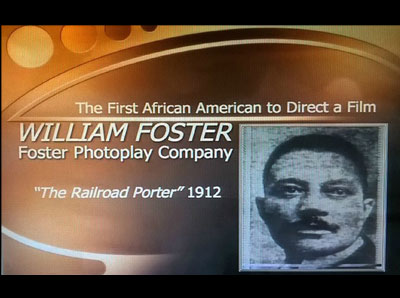

WILLIAM FOSTER, a.k.a. “JULI JONES” (1884-1940)

Attracted by the opening of Robert Motts’ Pekin Theatre in 1904, Foster moved to Chicago, where he became the Pekin Theatre’s business representative, a position that allowed him to view and book numerous black vaudeville acts.

Under the pen name of “Juli Jones,” Foster also began writing articles on black show business for various black weeklies, including the Chicago Defender; and by 1913, he decided to enter the movie profession himself. After scraping together enough money to found the Foster Photoplay Company, he produced his first short, a two-reel comedy called The Railroad Porter (also released under the title The Pullman Porter), starring Lottie Grady and Howard Kelly, both former members of Pekin’s stock company. The short, which opened strong at a few theaters in Chicago and later was shown in the East, was often featured on the same bill as Foster’s footage of a YMCA parade, now considered to be the first black-produced newsreel.

Foster had great hopes for black filmmakers and believed that “in a moving picture the Negro would off-set so many insults of the race—could tell their side of the birth of this great race.” So, he argued, it was the responsibility of the “Negro businessman . . . [to] put his race right with the world.” [2] As he had noted earlier in an article published in the black weekly Indianapolis Freeman (December 20, 1913), the motion picture allowed the “colored man” a means “for portraying the finer and stronger features of his particular life. . . . Our brother white is born blind and unwilling to see the finer aspects and qualities of American Negro life. . . . We must be up and doing for ourselves in our own best way and for our own best good.” [3].

Putting his own words into practice, Foster headed to Florida, where Lubin, Pathé, Kalem, and other licensed film manufacturers were making films, to evaluate the feasibility of building a studio there. But his optimism soon turned to frustration as he discovered that the major motion picture rental and distribution companies simply did not book black independent films into the widening market of white theaters, even though those same companies regularly booked white-produced films into the smaller number of exclusively black theaters. Moreover, while the major theatrical publications like Billboard, Variety, and Moving Picture World regularly advertised and reviewed black-cast films by white companies, they did not carry ads or run reviews of the films produced by early black-owned companies. This de facto economic boycott of the first black film producers, Henry T. Sampson [4] observed, “gave birth to a separate black film industry in the United States,” which “during the next forty years produced over 500 films featuring blacks which were shown in theaters catering to blacks with little distribution anywhere else.” But Foster would not be among those black filmmakers for whom he had earlier predicted such “phenomenal success.” Although he went on to produce a few more shorts, including The Fall Guy, The Barber, The Butler, and The Grafter and the Maid (also released under the title The Grafter and the Girl), he quit the motion picture industry in 1917 to become circulation manager of the Chicago Defender, which he helped to make one of the most widely circulated newspapers among blacks.

In 1928, hoping to resurrect his film career, Foster moved to Los Angeles, where he directed for the Pathé Studios a series of black musical shorts featuring such legendary performers as Clarence Muse, Stepin Fetchit, and the song-dance-and-comedy team of Buck and Bubbles. He also began selling stock subscriptions to revive and finance his Foster Photoplay Company and struggled bitterly “trying to get somewhere in this Business as a Producer” of “Pictures That Talk-Sing-Dance Reflect Credit” because, as he said, “if a colored producing co dont make the Grade now it will be useless later on after all the Big Co.s get merged up—they will set about controlling the Equipment then the door wil be closed [sic].” [5] Foster’s morose estimate was ultimately correct, and his production company released no new films.

The shorts that Foster produced before his company folded followed the established comedy formulas of the day; but, at the same time, they introduced elements from the black vaudeville stage. The Railroad Porter (1912), for instance, told the story of a young wife who, thinking her husband is out on his run, invites to dinner a well-dressed man who turns out to be a waiter. Returning home, the husband pulls out his gun; the waiter, according to the New York Age (September 25, 1913), “gets his revolver and returns the compliment… no one is hurt… and all ends happily.” And in The Barber (1916), a barber posing as a Spanish music teacher engages in a series of Keystone Kops-type of chases as he tries to evade an angry husband, the local police, and even an old woman, whose boat he overturns when he jumps in a lake to avoid capture. Foster’s shorts, however, were rarely distributed outside of the Midwest, and his players, despite their strengths as stage actors, failed to attract national recognition as film stars, even in the black press. Nevertheless, Foster’s efforts marked an important beginning for blacks in film. As Mark A. Reid [6] writes, Foster “broke with the ‘coon’ tradition established by Thomas Alva Edison’s Ten Pickaninnies (1904) and The Wooing and Wedding of a Coon (1905) as well as Siegmund Lubin’s Sambo and Rastus series (1909-1911)” and tried to create comedy that “would appeal to the widest segment of his [black] audience.” William Foster therefore remains a significant—if largely neglected—figure in black cinema history.