Z …is for

Zircon

Black characters, who had never before been prominently featured in a serial (much less one as thrilling, action-filled, and ambitious as Norman’s promised to be), had occasionally appeared in recurring minor roles in early films produced largely for white audiences. Those films, however, only reinforced contemporary racist comic stereotypes of figures that film scholar Daniel J. Leab described as “subhuman, simpleminded, superstitious, and submissive” to whites, frequently childlike in their dependence, with foolishly exaggerated qualities, including an apparently hereditary clumsiness and an addictive craving for fried chicken and watermelon. That type was best exemplified by characters such as Sambo or Rastus, who became a generic name for black stooges on screen in pictures such as How Rastus Got His Turkey (1910), How Rastus Got His Porkchops (1908), and Rastus in Zululand (1910).

An advance flyer that Norman developed especially for distributors, theater owners, and theater managers offered a fuller description of the episodes of Zircon, which centered on the adventures of John Manning, a young chemist and mining engineer at the Egyptian Potash Company, and his sweetheart, Helen Desmond, the daughter of his employer. After discovering a remarkable new substance that he names “Zircon,” Manning finds himself repeatedly threatened by “The Spider,” a criminal hired by the rival Potash Corporation. The Spider, who has secured a sample of Zircon, is determined to learn both the formula and the secret of its manufacturing process.

The Spider, it appears, has more tricks to play. Using a mysterious substance that makes him invisible, he attempts to flee again. Fortunately, Manning’s one-legged friend “Peg” secures some of the invisibility powder, and, rendering himself invisible, rescues Manning from the cabin in which he is being held just before it explodes. But this time, there is no escape for The Spider. He is killed by a piece of rock debris, and his gang is rounded up and captured. Manning is able at last to marry Helen, and with the rich deposits of potash he has discovered in the desert and the secret formula of Zircon, he forces the rival Potash Trust out of business and becomes a millionaire.

Some of the details of the episodes were familiar, drawing on names, scenes, and plot points from Norman’s earlier films. But Zircon aimed to exploit audience curiosity in other interesting and novel ways, particularly through its depictions of exotic but dangerous locales and of new technologies like airplanes, which figure prominently in two of the projected episodes.

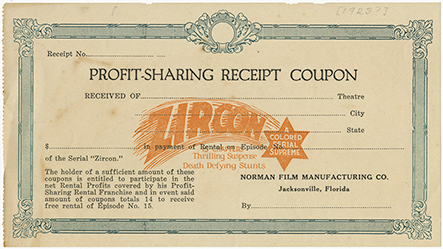

Although Norman had self-financed his earlier films, he realized that the production of a multi-part serial would be a significantly more expensive proposition. Claiming that each episode, or “chapter,” would cost almost as much as a feature film to complete, he settled on a different method of capitalizing his project. To each theater owner who bought into the “Profit Sharing Rental Franchise,” Norman promised double revenues: “first, from increased business in his theatre, and second, a participation in the net profits of the rental earnings of the serial, according to the pro rata amount of his rental.”

The “profit-sharing coupon” that Norman created to finance the serial promised big returns to theater owners and managers.

Given that Brooks was an accomplished actor who would draw moviegoers into the theaters, Norman was anxious to move ahead with production. At the same time, he understood that a fifteen-part serial, with two reels per episode, was a “risky experiment,” since it meant making the equivalent of six five-reel feature pictures. Compounding that experiment was the matter of distribution, which, even with strong advance bookings from race theaters, would be a huge challenge for an independent film producer. So, given the limitations of his own finances and the uncertainty of the future of race pictures, Norman abruptly abandoned the project, advising Brooks that he had decided to wait until things were “more ripe before springing [his] Star Series” and “the field was more open for Colored Pictures at a fair price.”

Survival Status: Never produced or released.

Director: Richard E. Norman (projected)

Release Company: Norman Studios (projected)

Cast: Clarence Brooks (proposed)

Episodes: (proposed) 1. The Spider’s Web. 2. The Wheel of Death. 3. The Poison Cloud. 4. The Desert Trap. 5. The Living Tomb. 6. The Crocodile’s Jaws. 7. The Sky Demon. 8. The Ship Killer. 9. Flame of Fear. 10. Tiger of the Sea. 11. Jungle Death. 12. Sands of Death. 13. Trail of The Spider. 14. The Vanishing Prisoner. 15. Millions.