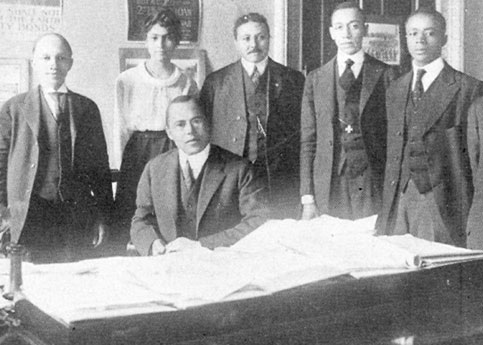

DR. EMMETT J. SCOTT (1873-1957)

The Birth of a Race Film Company

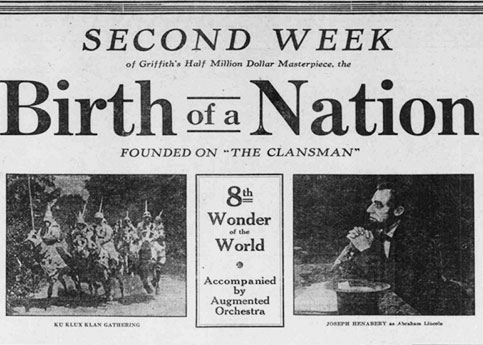

The Birth of a Nation was remarkable for the numerous innovations in cross-cutting, close-up and fade-out shots, effect lighting, iris shots, and split screens that Griffith introduced. But even more remarkable was the film’s highly sympathetic but grossly inauthentic portrait of idyllic life in the South, shattered by the Civil War and further threatened by carpetbaggers and Northern blacks who move into the area and exploit the Southern former slaves by unleashing their bestial natures and turning them into renegades, ultimately subverting the whole social order. The chaos created by these arrogant and aggressive blacks, Griffith suggests, necessitates the formation of the Ku Klux Klan, a group of white Christian knights who resort to terror and murder in order to set the world right again (a conclusion reinforced by Griffith’s final original allegorical shot, of Christ ascending into Heaven after having vanquished the God of War). A tremendous commercial success, The Birth of a Nation immediately found a large and receptive audience, even at the steep ticket prices that Griffith often charged.

Not surprisingly, the black response to such a viciously racist film was immediate and intense. Blacks decried The Birth of a Nation as sheer propaganda for the Ku Klux Klan, who actually used it as an organizing and recruiting tool. And they argued—correctly—that the film’s sympathetic portrayal of mob violence as a kind of divine retribution would lead to more lynchings. (The Klan itself had been revived and reinvigorated in 1915 by Joseph Simmons, an ex-minister “inspired” by the film. As Terry Ramsaye observed, “The picture… and the K.K.K. secret society, which was the afterbirth of a nation, were sprouted from the same root.”) [2]

Together with Booker T. Washington, Scott had been seeking a way to get involved in a black-controlled film production. Both men already knew something about movies from negotiations over the rights to shoot motion pictures on the Tuskegee campus. (D. W. Griffith, in fact, had at one point expressed interest in rights to old campus footage that he intended to use in a conciliatory prologue that he proposed to add to The Birth of a Nation.) After discussions with the NAACP over Lincoln’s Dream broke down, Elaine Sterne came to Scott, hoping that he could revive the NAACP’s interest and thereby salvage the project. But Scott was unsuccessful. Laemmle withdrew, as did several other producers that Scott had courted; and the dream of Lincoln’s Dream faded.

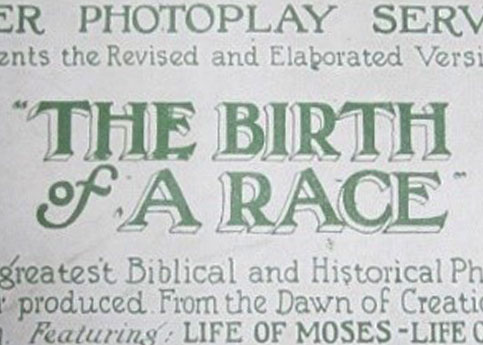

But financial mismanagement (including the fraudulent promotion and sale of stocks) and confused leadership created numerous and ultimately insurmountable problems. William Selig, the original producer, and his associates pulled out halfway through production, and Daniel Frohman, a New York veteran vaudeville producer, took over. Frohman, however, had a different concept of the film, and he immediately began shooting vast amounts of biblical footage in Tampa, where he had located a public park with mock Egyptian architecture—footage that had no relation to what the Selig Company had already shot. After Frohman dropped out, the film passed through the hands of several other white independent filmmakers before being completed at the Rothacker Film Manufacturing Company plant in Chicago. Scott and the other blacks involved saw themselves losing virtually all control of the venture; and eventually both Scott and Up from Slavery were “dumped.”[9]

In 1918, almost three years after it was first conceived, The Birth of a Race finally premiered at Chicago’s Blackstone Theater. Promoted as “The Greatest and Most Daring of Photoplays . . . A Master Picture Conceived in the Spirit of Truth and Dedicated to All of the Races of the World,” [10] the film was actually a complete flop. As released, it moved from the creation of the world to numerous other scenes from sacred history, all of which were re-created employing mammoth sets—and all to no artistic purpose. Instead of hailing black achievement within the context of the development of civilization, The Birth of a Race emphasized such decidedly anti-black images as the victimization of the Jews by the black army of the Pharaoh and the invasion of a white tribe by a black one, an incident that leads Noah to suggest that the “prejudice” that results from “living apart” is somehow tied to black failings; and instead of synthesizing the Gospels, the film carried forth the notion of racial separation in the person of a very white Jesus before cutting abruptly to the voyage of Columbus, the ride of Paul Revere, and (curiously skirting any visual depiction of slavery itself) the proclamation of emancipation by Lincoln. [11][12] Finally, according to Moving Picture World (May 10, 1919), in keeping with contemporary anti-German propaganda, “a disconnected war story [was thrown in] for good measure,” but it rendered the film both formless and essentially structureless and made it “a striking example of what a photoplay should not be.” That subplot, about Oscar and George Schmidt, two brothers in a German-American household divided against the war, tried to rouse patriotic fervor and celebrate America’s entry into World War I; but it may also have been meant to parallel the internecine North/South division in The Birth of a Nation. Like the Stonemans and the Camerons, who initially hold opposing beliefs about the principle of Southern sovereignty, the two Schmidt brothers respond in different ways to the world events: Oscar, the elder, decides to return to fight for the Kaiser; George, “a true blue American,” marries a girl employed in the munitions factory run by his father, goes overseas only after the United States enters the war, and successfully holds back several assaults by the vicious “Hun” (including an attack on a hospital by German forces led by his brother, whom he kills). As its garbled plot suggests, the film was indeed “the most grotesque cinematic chimera in the history of the picture business” (Variety, April 25, 1919).

Especially since only a portion of the film is extant, “we cannot know,” Cripps writes, “the details of the internal struggle over control of The Birth of a Race nor can we know the extent to which the surviving film represents the conscious intentions of its makers.” [13] But this much is certain: as Variety (December 6, 1918) noted, the film was started “on the premise of a nationwide defence of the Negro race”; a lot of stock was sold, largely to black investors who had been hustled into believing the film would have a legitimate race angle; “everything went along swimmingly” until America got into World War I and “the character of the picture was altered”; more stock was sold and “another scenario was written”; and ultimately the film shifted completely away from the aspirations, advancement, and achievement of blacks that were its original focus. [14] Moreover, a disillusioned Emmett J. Scott left filmmaking—although he continued to be prominent in the black community as the Army’s Assistant Secretary for Negro Affairs, a position in which he was able to help other filmmakers, and in various other leadership roles.