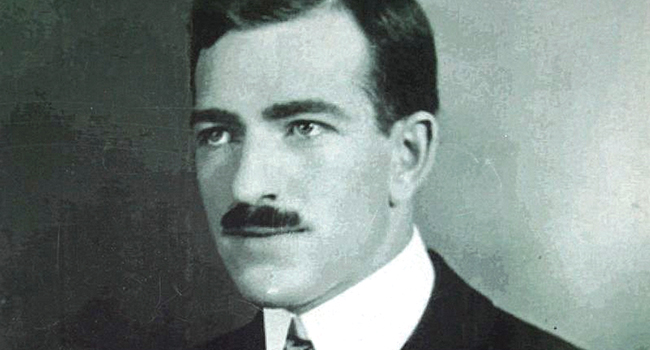

Silent filmmaker Richard Norman

Born in Middleburg, Florida, a rural town just outside Jacksonville, Richard Edward Norman (1891-1960) became enamored with the entertainment business early on. As a teenager, he worked at a Jacksonville theater, often playing piano, possibly as live accompaniment for some of the earliest silent films. After his parents’ split in 1910 came temporary moves to Kansas City, Kansas and Chicago where, by 1912, he found employment with several film production companies, first as a film developer and later as a cameraman and producer.

Over the years, Norman was associated with multiple film companies. Some he founded and ran himself while others he simply used as regional mailing addresses. Among them:

- Magic Slide Manufacturing Company, Kansas City, Missouri

- International Publicity Company, Kansas City, Missouri

- Superior Film Manufacturing Company, Des Moines, Iowa

- Capital City Film Manufacturing Company, Des Moines, Iowa

- Norman Film Manufacturing Company, Chicago, Illinois and later, Arlington, Florida (Arlington today is part of Jacksonville)

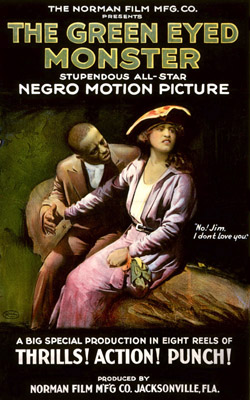

Many of Norman’s earliest productions were advertising and promotional projects for municipalities and civic and fraternal organizations. In documentary style, he covered everything from field meets to high society events. But his narrative filmmaking start was a series of films – all using the same script and footage of a train wreck and shot in some 40 or more towns, primarily throughout the Midwest and South. Believed to be one of the first profitable uses of stock footage in film, the train wreck scene was touted to cost upward of $80,000 – a fortune back in the day. These films bore one of three titles, The Wrecker, The Green Eyed Monster or The Man at the Throttle and featured not professional actors but local townsfolk.

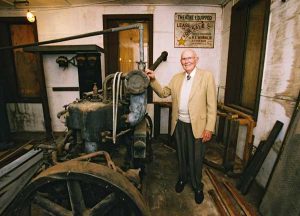

Says Norman’s son, Capt. Richard E. Norman, III in author Barbara Tepa Lupack’s Richard E. Norman and Race Filmmaking:

Capt. Richard Norman, III, son of silent filmmaker Richard Norman, standing with one of his father’s generators used to power filmmaking equipment.

“He would film, develop and edit the picture at cost inches Iowa lab headquarters and return to the city with the completed version. After expenses, Dad would split the profits on a 60-40 basis with the city and the local theatre showing the picture. (Sixty percent for him, forty percent divided between the city and theatre owner.) After the initial showings ended, the city would retain ownership of the film and they could use it later for promotional efforts. Nearly everybody involved would come and bring their friends to the screenings at ten or fifteen cents admission. Many saw the picture time and again and the local theatre manager would run it, run it, and run it. As a result, the profits were very good.”

It was while filming one of these productions that Norman cast a beautiful redhead as a bridesmaid in a fictional wedding scene. But he soon took Gloria des Jardin home to Jacksonville and made her his real-life bride.

Settled back in Jacksonville, Norman purchased the five-building Arlington property that had belonged to Eagle Film City and turned his efforts to an emerging genre of films. The movie industry’s first black filmmakers, including Oscar Micheaux and the Lincoln Motion Picture Company, were creating a stir, producing what then were called “race films,” made with all-black casts in non-stereotypical roles. While these films were largely shunned by mainstream white society, they were a source of pride among the black community. Norman, who was white, not only had a sincere, heartfelt desire to help improve race relations, he also saw a largely underserved business market among black filmgoers, as well as a wealth of beauty and talent among black stage and Vaudeville stars, who dreamed of making the leap to motion pictures. Unfortunately, the mainstream motion picture business was largely prejudiced, portraying black characters only in derogatory, villain, or step-and-fetch-it roles.

“My father was disheartened about the state of race relations at the time, both in real life and in the movies,” son Capt. Norman says. “And he saw an untapped market. So, he set out to help give the black community a stronger place on film, behind the cameras and in the theatres.”

In 1919, Norman remade The Green Eyed Monster with an all black cast and a comedic twist. The comedy version flopped, so he removed these scenes and edited the film into a five-reel, all-black drama. This proved a hit among African-American audiences and attracted letters from the top black actors of the time, all hoping to star in the next Norman Studios film.

Later films included Regeneration (1923) starring Stella Mayo of the famed Mayo Family Magicians; Black Gold (1928), a greed- and love-fueled story surrounding the oil business; and The Flying Ace (1926), Norman’s most celebrated film (restored and housed at the Library of Congress today).

Billed as “the greatest airplane thriller every filmed,” The Flying Ace was shot entirely on the ground, but was lauded for its stunts and camera tricks. Much of Norman’s inspiration came courtesy of headlines about black aviators including Bessie Coleman. He had spoken with her about making a film of her stunt flying exploits shortly before her untimely death in a plane crash near Jacksonville’s Atlantic shore.

Richard Norman’s legacy is that of a man who sought to integrate an industry long before the mainstream would embrace it, and to produce films with story lines and high-quality acting and production values that stand the test of time. Screenings of The Flying Ace still today have audiences laughing out loud and in awe of the production values of a nearly century-old film.

Richard Norman was much more than a filmmaker – he was a visionary, both professionally and civically. Though his films may not be considered among the “greats,” they were groundbreaking. As a white filmmaker daring to produce black-cast and crewed films with positive, family-friendly storylines, he took great risks both professionally and personally. Yet his films were loved by both black and white audiences, says son Capt. Norman, who tells tales of playing on his father’s film sets as a very young boy, including hiding from playmates in the hollow of one of The Flying Ace‘s stunt planes.

Norman’s purchase of the Eagle City Film Center extended Jacksonville’s era of silent film production that had begun in 1907 when the Kalem Company of New York filmed its first on-location picture in Northeast Florida, and largely whittled down by 1920, with the most successful companies heading westward to Hollywood. His work here provided a bridge to the next generation of filmmakers who chose the area and his unique story continues to inspire film enthusiasts today. In the future his studio will provide a center for youthful filmmakers to practice their craft.

Today, Norman’s five-building silent film studio complex still stands in the heart of Jacksonville’s historic Old Arlington neighborhood. Working in tandem with the City of Jacksonville, the Norman Studios aims to support the restoration and reopening of the property as a bustling tourism and film education center.