By Cher Davis

By Cher Davis

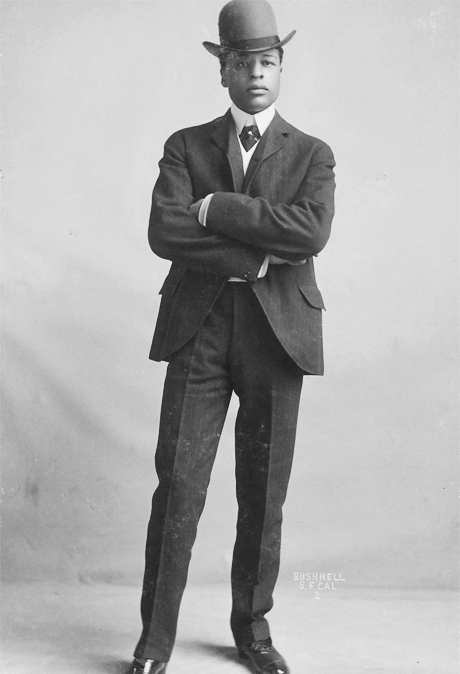

As a Black actress in today’s entertainment industry, I have often felt duty-bound to pay homage to those individuals who have, throughout history, paved the way for ongoing generations of Black performers to be recognized for their talent, not for the color of their skin. One such individual is Egbert Austin Williams, better known as “Bert” Williams.

Bert Williams was born in Nassau, Bahamas in 1875, and his family later moved to California. Due to failing health, the family fell on hard times, so after graduating from Riverside High School in 1893, Williams abandoned his studies at the civil engineering program at Stanford University to become an entertainer. Turning to his self-taught musical and mimicry skills to earn a living, he joined different West Coast minstrel shows, including Martin and Selig’s “Mastodon Minstrels”. It was from this time that he became long-time friends with George Walker, and the two went on to become one of the most successful comedy teams of their era, both domestically and abroad, even playing a command performance of their jointly-produced comedy In Dahomey in England for King Edward VII in 1903.1

Williams and Walker performed in burnt-cork blackface, as was customary during the vaudeville era, and they met with sharp criticism for doing so from some of the leading black newspapers at the time. In contrast, a careful review of the pair’s body of work indicates that they actually sought to distinguish their act from the many white minstrels also performing in blackface. Over time, it seems they were constantly required to weigh their efforts to create a less racial, more eclectic style of comedy against the fact that they performed before many white audiences in an era where segregated audiences were commonplace. For example, while In Dahomey was considered controversial for Williams’ famous version of the cake walk (a dance that is a throwback to the times of slavery), Abyssinia, which premiered a few years later, received sharp criticism from white critics seemingly because the performance strayed from the usual racial overtures with which white audiences had been accustomed.

In describing his experiences, Williams wrote:

“People sometimes ask me if I would not give anything to be white. I answer … most emphatically, ‘No.’ How do I know what I might be if I were a white man? I might be a sandhog, burrowing away and losing my health for $8 a day. I might be a streetcar conductor at $12 or $15 a week. There is many a white man less fortunate and less well-equipped than I am. In fact, I have never been able to discover that there was anything disgraceful in being a colored man. But I have often found it inconvenient … in America.”2

“People sometimes ask me if I would not give anything to be white. I answer … most emphatically, ‘No.’ How do I know what I might be if I were a white man? I might be a sandhog, burrowing away and losing my health for $8 a day. I might be a streetcar conductor at $12 or $15 a week. There is many a white man less fortunate and less well-equipped than I am. In fact, I have never been able to discover that there was anything disgraceful in being a colored man. But I have often found it inconvenient … in America.”2

George Walker died from syphilis in 1911, thus bringing Bert Williams to a turning point in his career where he began to establish himself as a solo performer.

In lieu of the racial struggles he endured during his historic career, Bert Williams was a man of significant “firsts” and “bests”. Together with Walker, he produced, wrote and starred in In Dahomey, the first Black musical comedy to open on Broadway. Part of the inspiration for the show was Williams’ copy of a 1670 book, Africa, in which author John Ogilby traced the history of the continent’s tribes and peoples. His work for this production made Williams the first black American to take a lead theatrical role. In his early days as a single act, Bert Williams was the first Black to rise to top-billing status as a star comedian, despite numerous attempts from rival white vaudeville performers to bully theater managers into reducing his billing. During the span of time while he was a performer on Broadway in New York, and although he lived at one of the city’s top hotels, he always had to ride the service elevator to his suite rather than come in by the main entrance.

In the face of the racial indignities he experienced, Williams also became the first Black comedian to ever appear in the cinema. He debuted on screen in the 1914 all-black silent film Darktown Jubilee, during which the screening was rejected so vehemently, it was quickly taken out of circulation by the distributor, Biograph. In 1915, the Biograph Company gave Williams the green light to produce, write, direct, and star in two Biograph films: The Natural Born Gambler (1915)3 which features his most famous poker player pantomime routine, and Fish (1916). This made him the first Black-American ever to have full control and produce his own films for a general audience. Known most popularly for his signature theme “Nobody” from the production Abyssinia (1906) that he co-created with Walker, Williams retained a relatively exclusive reputation for the song in an era when the most popular songs were simultaneously promoted by several artists. The song was recorded through Columbia Records, remaining in the company’s catalog into the 1930s which made it one of the best-selling recordings at that time with sales estimated between 100,000 and 150,000 copies. This success combined with other numerous Columbia recordings such as “Everybody Wants a Key to My Cellar”, “Save a Little Dram for Me”, “Ten Little Bottles”, and the smash hit, “The Moon Shines on the Moonshine” made him by far the best-selling black recording artist before 1920. Williams had four songs that shipped between 180,000 and 250,000 copies in 1920 alone in an era when just tens of thousands of copies was considered a successful major label release. Williams, along with Al Jolson and Nora Bayes, was one of the three most highly paid recording artists in the world.4

From 1910 to 1919, he is most memorable for his performances as the first black member in Ziegfeld’s Follies, and during that time he is considered to have been the highest-paid black performer in history. Despite 20 plus years as one of the most successful and respected stage performers in New York, Williams had never been invited to join Actors Equity. When Actors Equity went on strike in August 1919, the entire Follies cast walked out, except for Williams, who showed up for work that day because had not been told about the strike. Reportedly, it was thanks to the sponsorship of his white fellow cast member W. C. Fields that Williams was finally allowed as the first black performer to join the organization.

From 1910 to 1919, he is most memorable for his performances as the first black member in Ziegfeld’s Follies, and during that time he is considered to have been the highest-paid black performer in history. Despite 20 plus years as one of the most successful and respected stage performers in New York, Williams had never been invited to join Actors Equity. When Actors Equity went on strike in August 1919, the entire Follies cast walked out, except for Williams, who showed up for work that day because had not been told about the strike. Reportedly, it was thanks to the sponsorship of his white fellow cast member W. C. Fields that Williams was finally allowed as the first black performer to join the organization.

Following his last appearance Follies in 1919, his career took a downturn from that point. The constant racial prejudice he continued to face propagated his personal battles with insomnia, depression and alcoholism. On February 27, 1922, Williams collapsed onstage while touring with the production of “Under the Bamboo Tree” during a performance in Detroit, Michigan, which the audience initially thought was part of his comedic bit. He returned to New York, but his health worsened. He died at his home in Manhattan, New York City on March 4, 1922 at the age of 47. On March 8, 1922, Williams was the first black American to be honored with a Masonic funeral service by an all-white Grand Lodge, the Grand Lodge of Free and Accepted Masons of the State of New York.

I think that if Bert Williams were alive today, he would decry the inequalities of wealth, income and homeownership that persist in today’s economy5,6 even with every victory to date achieved in the name of civil rights. With the more open public forum available in today’s society, I’d like to think that had he survived into the era of “talkies”, he would no longer remain silent in more ways than one. I believe especially because he would no longer be forced to conform to the blatantly racist industry standards of the past that he would speak out against the subtle yet tangible obstacles that still remain within today’s entertainment industry. Films like Bamboozled and Dear White People remind contemporary audiences about the elephant in the room that many folks, Caucasian and Black alike, are uncomfortable with: the fact that in this day and age, race continues to be a discriminating factor when considering opportunities for the advancement of people of color. Today, Bert Williams continues to be a key figure in the history of African-American entertainment as one of the greatest vaudeville performers in the history of the American stage.

1 Jensen, David A., Tin Pan Alley: an encyclopedia of the golden age of American song, (2003).

2 Brooks, Lost Sounds (2004), p. 174.

3 Public domain copy available on The Internet Archive website: https://archive.org/details/natural_born_gambler

4 Brooks, Lost Sounds (2004), p. 140.

5 Vega, Tanzina, (June 27, 2016). Blacks still far behind whites in wealth and income. Retrieved January 22, 2017 from the CNN Money website: http://money.cnn.com/2016/06/27/news/economy/racial-wealth-gap-blacks-whites/

6 (June 27, 2016). On Views of Race and Inequality, Blacks and Whites Are Worlds Apart. Retrieved January 22, 2017 from the Pew Research Center, Social & Demographic Trends website: http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2016/06/27/on-views-of-race-and-inequality-blacks-and-whites-are-worlds-apart/

W. C. Fields said, after Williams’ death, Williams “was the funniest comedian I ever saw, and the saddest man I ever knew.”

Source: Turner Classic Movies

Life and it will get better, either sooner or later.