by Mitch Hemann

This weekend marks the 90th anniversary of the passing of Bessie Coleman, and Norman Studios would like to honor her incredible legacy as America’s first Black Female Aviator. Not everybody knows Coleman’s inspiring story, and even fewer know that she has a connection to Richard Norman.

Bessie Coleman was born January 26th, 1892 in Atlanta TX and was the tenth of thirteen children to George and Susan Coleman. Her parents were sharecroppers and lived a very hard life. When Bessie was two, hoping for a better life, her father moved the family to Waxahachie TX, where he bought a little bit of land and built a house. Bessie started school there at the age of six, and had to walk 4 miles every day to her all black school. She excelled in her studies and had a knack for math.

1901 was a turning point for the family. George Coleman, who was half Cherokee, could no longer stand the racial barriers one had to endure in Waxahachie and left for Oklahoma (known as Indian Territory at that time). Unable to convince his family to join him, he left Susan behind to care for the children on her own. She quickly found work as a cook and housekeeper and Bessie assumed most of the responsibilities around the house. Bessie divided her time between school, housework, and church. That is, until the cotton harvest arrived. All hands were needed then, so the family worked together in the fields.

1901 was a turning point for the family. George Coleman, who was half Cherokee, could no longer stand the racial barriers one had to endure in Waxahachie and left for Oklahoma (known as Indian Territory at that time). Unable to convince his family to join him, he left Susan behind to care for the children on her own. She quickly found work as a cook and housekeeper and Bessie assumed most of the responsibilities around the house. Bessie divided her time between school, housework, and church. That is, until the cotton harvest arrived. All hands were needed then, so the family worked together in the fields.

When Bessie was twelve, she was accepted into the Missionary Baptist Church. She completed all eight grades and was hungry for more. She scraped some money together and, in 1910, enrolled in the Colored Agricultural and Normal University in Langston Oklahoma. Sadly, she was only able to complete one term before running out of money. She had no choice but to return to Waxahachie and her previous life as a laundress. She remained there until 1915 when, at the age of 23, she saw another opportunity to escape and moved in with her brothers Walter and John in Chicago while she looked for work.

The many barbershops and beauty salons that dotted Chicago’s South Side motivated her to become a beautician, and she found work as a manicurist in spots along an area known as The Stroll. But it was her brothers’ teasing that inspired her to fly. Both of them had served in World War I and they would taunt her about French women flying planes and having careers of their own overseas. Bessie, who always wanted to “amount to something”, developed a burning aspiration to become a pilot.

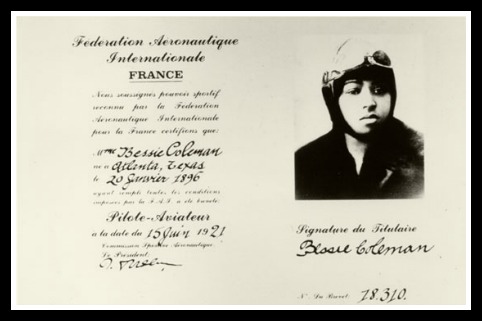

There was one problem; nobody in America would teach a black woman to fly. So, following the advice of her friend Robert Abbott, publisher and editor of the Chicago Defender, Bessie headed to France to attend the Ecole d’Aviation des Freres Caudon at Le Crotoy in the Somme. She completed the ten month course in just seven months and received her license from the Federation Aeronautique Internationale (FAI) on June 15, 1921. She then spent three more months training before heading back to the states, where she received a surprising amount of attention from the press. Deciding to pursue a career as a trick pilot and entertainer, Bessie returned to Europe once more for advanced training.

To establish herself and her career in the states, Coleman needed plenty of publicity. She cleverly created an image for herself, complete with a military style uniform. Her first air show was on September 3, 1922 at Curtiss Field on Long Island, where she was billed as the “World’s Greatest Woman Flyer”. She made appearances all over the country, and earned enough money to make a down payment on her very own plane. She also gave a series of lectures in Georgia and Florida and opened a beauty shop in Orlando to raise funds to fulfill her dream of opening an aviation school. All the while she continued to fly and perform. One sidenote about Coleman’s shows that’s worth mentioning was that she refused to perform unless the audience was integrated and could all use the same gates.

Eventually, Bessie was able to make the final payment on her plane in Dallas. It was a JN-4 (or Jenny) made by the Curtiss Southwestern Airplane and Motor Company. Excited, she prepared to have it flown to Florida for her next performance scheduled in Jacksonville FL on May 1st, 1926.

Eventually, Bessie was able to make the final payment on her plane in Dallas. It was a JN-4 (or Jenny) made by the Curtiss Southwestern Airplane and Motor Company. Excited, she prepared to have it flown to Florida for her next performance scheduled in Jacksonville FL on May 1st, 1926.

The plane arrived in late April and, on the evening of the 30th, she and her mechanic decided to take it up for a test flight. Sadly, this was to be Coleman’s final flight. Once in the air, the plane malfunctioned and her mechanic lost control. Bessie, who was in the backseat without a seatbelt, was thrown from the cockpit. In a matter of seconds, the woman who grew up picking cotton in rural Texas and dreaming of a better life was gone. Thousands mourned her passing at memorials both in Orlando and Chicago.

In 1929, her dream of starting a flying school for African Americans was realized when aviator William J. Powell established the Bessie Coleman Aero Club in Los Angeles. Even today, Coleman’s legacy and pioneer spirit lives on, and has inspired countless people who dare to dream big and shatter racial boundaries.

The significance of Coleman’s life and death had a lasting impression on Richard Norman. It turns out Bessie was familiar with his films and was interested in doing a biopic about her life. It’s believed she wanted to meet Norman to discuss this project while in Jacksonville. In fact, Norman and Coleman shared a friend who worked to promote the both of them by the name of D. Ireland Thomas. Thomas actually wrote Norman about her upcoming appearance in Jacksonville and suggested they partner on a project. Sadly, their meeting was fated never to happen. Still, Norman found inspiration in her story and began working on a new film that would be an aviation adventure, with a female lead whose character was based on Coleman. That film would be The Flying Ace, the only known surviving film of Richard Norman’s, and its very existence owes a lot to Bessie Coleman and her lasting legacy.