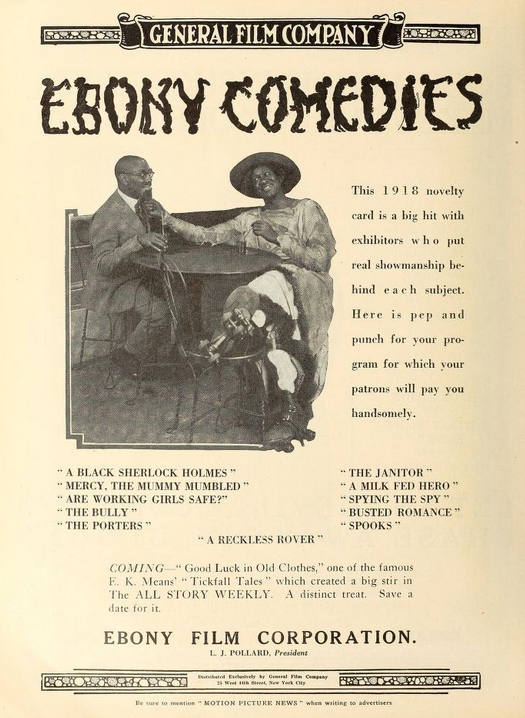

The story of the Ebony Film Corporation is one that was plagued with trouble throughout its short lifespan. Nevertheless, they produced a handful of films that even today are deemed important for their contribution to the discussion of race relations.

Located in Chicago’s Logan Square neighborhood on the corner of California and Fullerton, the studio first opened its doors in 1915 under the name Historical Feature Film Company. The studio was white-owned and produced slapstick comedies for both white and black audiences. The films were filled with every racial stereotype imaginable. Consequently, fresh on the heels of public outcry to D.W. Griffith’s terribly demeaning The Birth of a Nation (1915), black audiences promptly turned their backs on them and their reputation suffered. The company responded by changing their name to Ebony Films and hiring an African American staff to run the show in 1917.

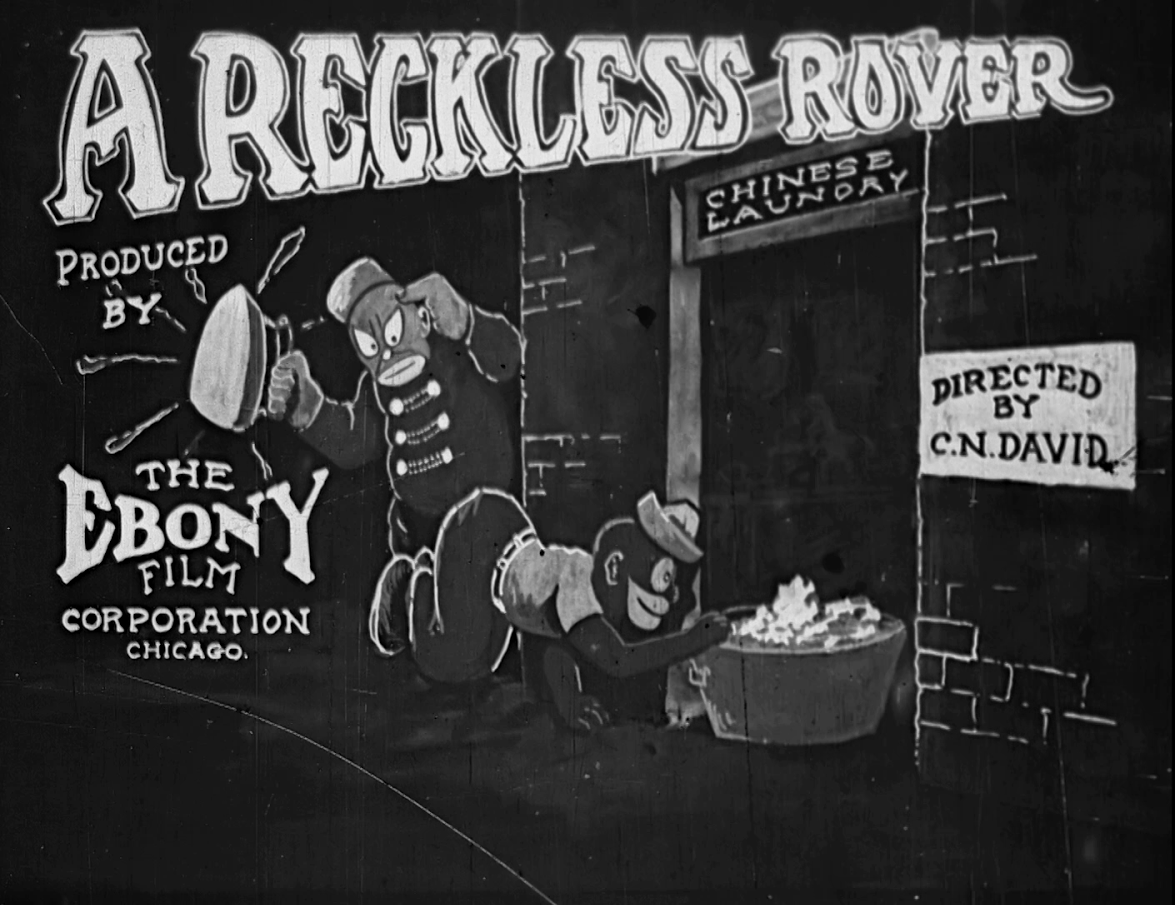

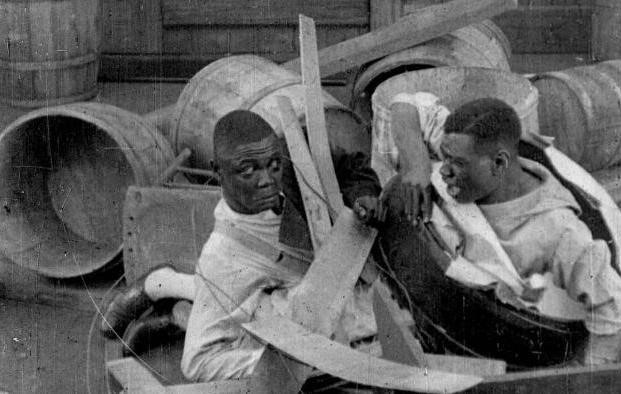

The company boasted 40 players from the George M. Lewis Stock Company. Among them was the very talented Sam Robinson, younger brother of Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, who starred in a number of shorts including A Black Sherlock Holmes, The Bully, and the Keaton-esque A Reckless Rover (1918).

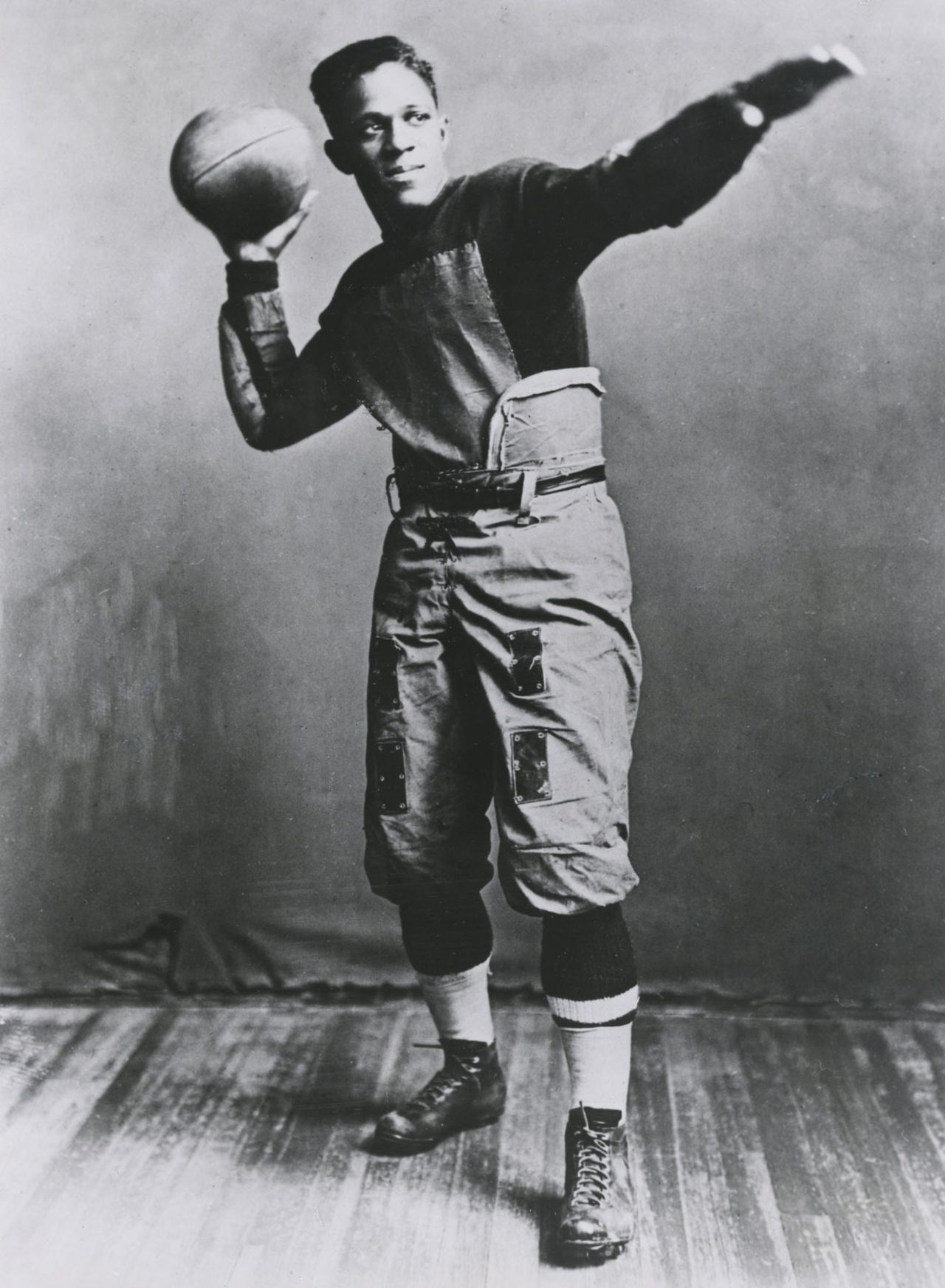

But perhaps the most important players in the Ebony story were the Pollard brothers, who grew up in the Rogers Park area of Chicago. Luther J. Pollard was given the title of president and general manager. He was also an active partner and did some directing. His brother, Frederick Douglas “Fritz” Pollard, would assist him as talent scout and casting agent, and would later make history as the NFL’s first black quarterback and head coach. Additionally, Fritz Pollard would go on to establish New York City’s first black owned newspaper, The New York Independent News.

Luther Pollard’s role at Ebony was complicated. Many saw him as a “colored front man” for a white-owned company, but it would be a disservice to label him as such. He was a strong advocate for positive black roles in film, and tried to steer the company in a new direction. In fact, in a letter to George P. Johnson of the Lincoln Motion Picture Company, Pollard wrote that his comedies “proved to the public that colored players can put over good comedy without any of that crap shooting, chicken stealing, razor display, water melon eating stuff that the colored people generally have been a little disgusted in seeing. You do not find that stuff in Ebony comedies.”

But the damage had already been done. Because it was white-owned, Ebony’s comedies were screened in both white and black theaters and, while white audiences ate up the low brow humor, black audiences were outraged at what they viewed as the same old stereotypes. It didn’t help that Ebony distributed its earlier, less flattering Historical Feature shorts under their new name. This tarnished the company’s reputation. There were numerous letters of protest published in The Chicago Defender and the paper itself began to condemn the studio and call for a boycott. Any efforts the Pollard’s would make towards progress were in vain and, despite a last ditch effort to distribute films with integrated casts, Ebony closed its doors in 1919.

Over the years, Ebony’s films have been reexamined for their historical significance and some historians believe that they are relevant in telling the story of black entertainment during that era. Spying The Spy (1918), for example, has been viewed as a deliberate response to Griffith’s unfortunate The Birth of a Nation. And it has been suggested that Two Knights of Vaudeville (1915) contains some subtle symbolism aimed at demonstrating how blacks were treated in the theater. One example is the black dog featured in the film, which, along with the black characters, is not allowed in the venue. The intent may have been to suggest that African Americans were treated no better than dogs. All in all, Ebony’s story is unfortunate, but it yielded some decent films that certainly have a place in the canon of African America cinema.

I am interested in “Black Gold” (1928) filmed in Tatums, Oklahoma. My grandfather was with Pure Oil at the time and living in Fort Worth, Texas. I can’t find any information about drilling around Tatums at that time: what companies were involved and what tracts they were drilling on. “Black Gold” might well have been filmed at a Pure Oil facility. BTW, my grandfather rejected the racism that was a fact of life in white society at the time. He might well have learned from the production of “Black Gold,” since a white man, Norman, was there to mediate between him and the actors and locals.

Excellent…Informative.