By Mitch Hemann

Marie-Georges-Jean Méliès was born on December 8, 1861, in Paris France. His father, Jean-Louis-Stanislas Méliès, was a shoe maker, and by the time Georges came along he had a successful business and amassed a bit of wealth. From the start, Georges had a very active imagination and was quite creative. His father, who hoped he would follow in his footsteps, disapproved of his interests and put him to work in the family business. This is how he learned to sew. As a reward for obeying his father’s wishes, he was able to attend art classes to satisfy his flights of fancy. Young Georges had a passion for drawing and puppetry. He even built imaginative sets to put on his own marionette performances. But it was magic that would eventually capture his heart.

After three years of mandatory military service, Georges was sent to London to work for a friend of his father’s. It was there he started frequenting the Egyptian Hall, a theater owned by illusionist John Nevil Maskelyne. He became enamored with stage magic and Maskelyne would have a great influence on him. Méliès returned to Paris and expressed a desire to study art at the École des Beaux-Arts. His father refused, so he went back to work at the shoe factory. He continued to pursue his interest in magic by taking lessons and regularly attending performances at the Théâtre Robert-Houdin, which was owned by the magician Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin. When his father retired in 1888, Georges sold his shares of the family business in order to buy the Théâtre Robert-Houdin. Attendance was low at first, due to outdated acts, but Méliès would create many new illusions and book a variety of other acts and the seats began to fill again. His most beloved illusion was the “Recalcitrant Decapitated Man”, where he would appear to remove his own head while it continued speaking. The theater kept him happy and busy. A jack-of-all-trades, Méliès wrote, directed and produced the acts, as well as designed the sets and costumes. He enjoyed great success, but he was about to stumble upon his greatest breakthrough.

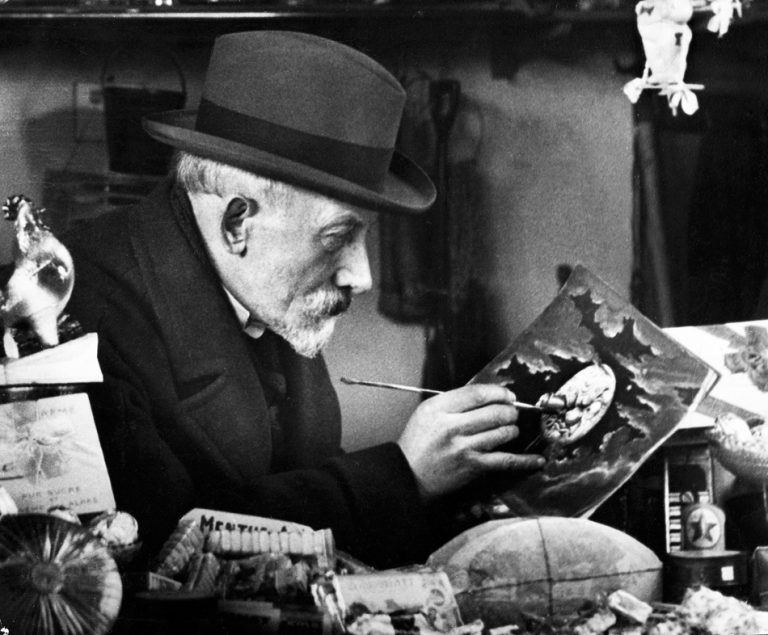

Méliès at his studio in Montreuil.

In 1895, Méliès received an invitation to a private event hosted by the Lumière brothers. It was there they demonstrated their Cinematograph, a motion picture camera which doubled as a projector, and Méliès was in awe. He immediately offered the brothers 10,000 francs for their machine, but they refused. Desperate, Méliès searched all over Europe for a similar device of his own. His quest finally brought him to London where he was able to purchase an Animatograph, a similar machine invented by Robert W. Paul. He also bought a few short films from Paul and he was off and running.

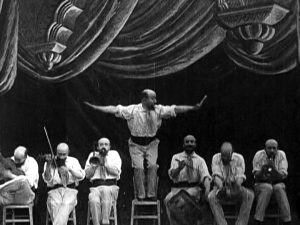

The One Man Band (1902)

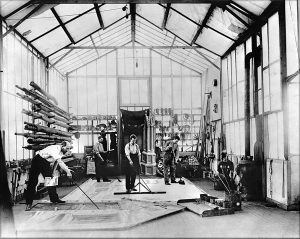

Always curious, it wasn’t long before Méliès was modifying his new toy so that it could operate as a camera. There were no processing labs in Paris, so he had to buy the film in London and develop and print it himself. In 1896, he founded the Star Film Company and patented his new Kinètographe Robert-Houdin, but the design was crude at best. It was so loud, he would refer to it as the “coffee grinder” or “machine gun”. A year later, there were several better cameras on the market, so he abandoned his own invention and purchased them instead. He built his own studio made entirely of glass, in order to make the best use of sunlight. This was the start of a career in which he directed over 500 films in less than 20 years.

The Four Troublesome Heads (1898)

Méliès would become instrumental in the world of special effects. Before he came along, audiences were viewing fairly straight forward and common scenarios that were already losing their appeal. Méliès, who had a penchant for fantasy and illusion, would create many camera tricks and effects that would change cinema forever. One such effect was discovered quite by accident when his camera jammed for a moment and then resumed shooting. The result, as he described, was a bus turning into a hearse and women turning into men. The “stop trick” had been used before by Thomas Edison, but it was new to Méliès and he would go on to use it in The Vanishing Lady (1896). Another of his innovations was to shoot through an aquarium to create underwater scenes. He would use this trick in several of his films. He developed many other special effects still used today, like double exposure, matting, and the split screen. His 1899 adaptation of Cinderella is the first film to use a dissolve and was his first major success.

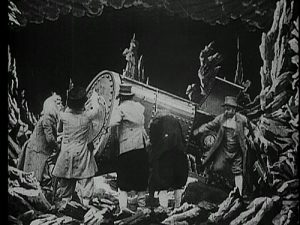

A Trip To The Moon (1902)

Méliès would have another breakthrough in 1902, when he directed the first ever science fiction film. A Trip To The Moon was inspired by the writings of H.G. Wells and Jules Verne, as well as composer Jacques Offenbach’s operetta, Le voyage dans la Lune. Audiences fell in love with the story of an expedition to the moon, and all the strange and magical things the explorers would encounter before plummeting back to earth. One of the films most beloved scenes, in which the rocket crashes into the eye of the moon, is recognized even today as one of the most iconic images in cinema. Méliès hoped to ride the film’s success all the way to America, but he soon discovered that Thomas Edison and other filmmakers had made their own copies of his film and were already profiting off of his hard work. He tried to set up an office in New York to combat the imitators and plagiarists, but it was too late. Méliès had learned a hard lesson about the darker side of the industry, and he was about to receive another one. One that would eventually be his downfall.

A Trip To The Moon (1902)

In 1910, Méliès signed a deal with Charles Pathé and his company Pathé Frères. In exchange for a large sum of money, Pathé would edit and distribute his films. As part of the unfortunate deal, Pathé also held the deeds to both Méliès’ home and studio. Méliès began work on some of his most ambitious films, like Baron Munchausen’s Dream (1911), The Diabolical Church Window (1910) and The Conquest of the Pole (1912). But the industry was changing, and the audiences were changing along with it. Sadly, these later films were not as successful, and Pathé began to tighten their control over his work. This would include cutting his 54 minute second adaptation of Cinderella (1912) down to 33 minutes in order to make it more profitable. Despite the effort, the film would not enjoy the success of his earlier 1899 version.

Growing more and more dissatisfied with their arrangement, Méliès broke his contract with Pathé. Méliès was now bankrupt, and had no way of paying his debts to Pathé. His one stroke of luck came when a moratorium was declared as World War I was breaking out, preventing Pathé from taking his properties. But his film career was most certainly over, and he was about to receive another devastating blow. In 1917, the French Army converted his beautiful glass studio into a hospital for wounded soldiers. Even worse, they confiscated hundreds of his original prints which were melted down for the war effort. The celluloid was used to make boot heels for the soldiers. This meant that Méliès’ incredible body of work would literally find itself being trampled underfoot. By 1923, the Théâtre Robert-Houdin was torn down, and Méliès was selling candy and toys at a shop in the Gare Montparnasse railroad station in Paris. It seemed as though the legacy of one of the industry’s greatest pioneers was all but forgotten.

Méliès doing what he does best.

But the tables were about to turn for Méliès. In 1929, a gala retrospective was held at the Salle Pleyel to celebrate his life’s work. Méliès would describe the event as “one of the most brilliant moments” of his life. Not long after, he was made a Chevalier de la Légion d’honneur and was awarded the medal by none other than Louis Lumière himself, who referred to Méliès as the “creator of the cinematic spectacle”. Méliès was finally getting his due.

In 1932, Georges was admitted into La Maison du Retraite du Cinéma, a retirement home for luminaries of the film industry. It was there that he would make his last great contribution to the cinema, when some of his friends rented a building on the property to store their vast film collection and entrusted Méliès with the key. That collection would later become the Cinémathèque Française, a massive archive of films, documents and other memorabilia, and Méliès would be its first conservator.

On January 3, 1938, Georges Méliès died of cancer at the age of 76. His last known words were, “Laugh, my friends. Laugh with me. Laugh for me, because I dream your dreams”. Georges Méliès, the dreamer of dreams, will be forever remembered as the father of special effects, and for bringing magic to the movies.